Executive Summary: Volume 2

The second volume of NAWRB’s Women in the Housing Ecosystem Report (WHER) includes an in-depth overview of the opportunities and obstacles women professionals face in the housing and real estate ecosystem, from the rate of women’s entrepreneurship and women’s roles in family offices and intergenerational wealth transfer, to female representation in the C-suite and gender diversity across the globe. The report provides insight regarding the most effective strategies for increasing diversity in the corporate sphere and highlights the need for diversity and inclusion efforts at all levels of employment.

Key Findings

Focus on Female Representation at All Levels of Employment

Methods for increasing gender diversity need to focus on all levels on employment, not just at the top. Recent efforts to increase gender diversity have placed priority on hiring more women at executive-level positions. Although this is an important aspect in effecting change, it is not enough to guarantee gender diversity in the long term.

Increasing women’s representation in the workforce at the professional level and above requires more integrated practices and policies. If we do not focus on women’s representation down the pipeline, from the C-suite to entry level positions, women will only make up 40 percent of the professional workforce within the next decade.

Women of Color Face Greatest Obstacles in Advancement

While the number of businesses owned by women of color have grown exponentially over the past 20 years, women of color face greater obstacles in terms of career advancement, and have unique experiences due to the intersection of race and gender.

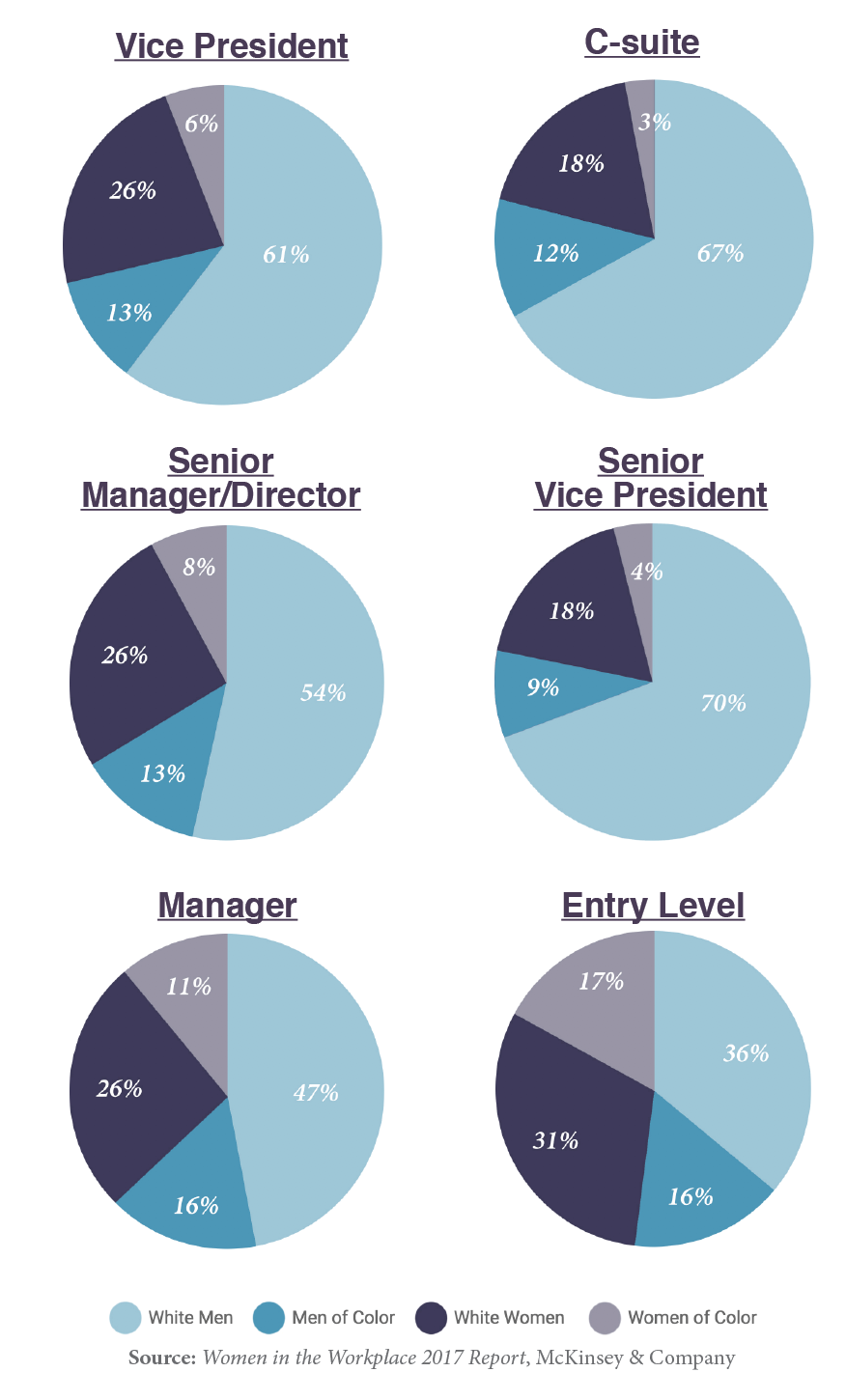

Women of color remain significantly underrepresented in the corporate pipeline compared to men, and this disparity is not due to company attrition or women’s lack of interest in advancement. According to McKinsey & Company’s Women in the Workplace 2017 report, women make up 1 out 5 C-suite leaders, while women of color make up 1 out of 30.

Women of color have a more arduous path towards the executive level, often receiving less support from their managers in career advancement and getting promotions at a lower rate than their peers. These disadvantages create a poor perspective of the workplace and the opportunities available to them, but it does not diminish their dreams of having a seat at the table.

Company Culture Affects Effectiveness of D&I Initiatives

D&I initiatives are only effective if they are adopted as part of a company’s practices and ethos. There can be disagreement within an organization about the necessity and effectiveness of these efforts, from entry-level to the executive level, which should be discussed in an open, encouraging environment. If a company’s top executive and managers do not make D&I a priority, then it cannot be expected that other employees will.

D&I initiatives can effect change when all genders and employment levels work together to ensure equal opportunity within their organizations. As Mercer’s When Women Thrive report states, women thrive when men are engaged in D&I efforts. Gender diversity needs to be adopted by all employees because having a diverse workforce helps the entire company succeed.

Main Characteristics of Effective Gender Diversity Strategies

Effective gender strategies are those that take place at the individual and organizational level, as stipulated in Mercer’s When Women Thrive report. At the individual level, an effective strategy at increasing diversity needs to be led by passionate leaders who drive change through open communication and exemplary behavior; adopted as a personal commitment by both employers and employees; and created to ensure perseverance over time by focusing on more than just hiring more women at the top.

At the organizational level, organizations should first conduct research outside and within their company to figure out which practices are creating change and which efforts need to be improved. This might involve creating better leave and flexibility programs for their employees, reconfiguring leadership roles that complement women’s unique competencies, and training their managers to effectively administer leave and return-to-work processes.

Women are able to thrive in the workforce when organizations have a strong pay equity process, as they are more likely to have greater female representation when they also have a team dedicated to gender equality. It is crucial for organizations to assist a diverse workforce with programs that meet their unique health and financial needs, which vary between men and women.

Thinking Beyond Quotas

An effective method of increasing women’s representation will require more than meeting quotas. Placing experienced women on boards and appointing them to senior executive positions is important as we need more diverse voices at the table where major decisions are made. However, for women professionals to be perceived as more than just token hires, there needs to be a culture shift in companies that embraces diversity and inclusion.

More women need to be hired at entry and management levels, and given opportunities to rise through the ranks, from management to the C-suite. Once current executive women leave their positions, we need to create a pathway for other women to take their place—a place they earn by merit, and through the visible hard work they did to get there.

Entrepreneurship is a tried and true way of generating wealth and women are driven to self-employment for its other benefits as well, including the ability to be their own boss, work flexible hours and do something that they are passionate about and enjoy.

As more women become their own bosses, they compose a larger share of small businesses, of which 80 percent have no employees other than the owner, in the United States. In 2013, there were 28.8 million small businesses in the United States. Data from the United States’s Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy reveals that women owned 12.3 million firms, which is about 45 percent of all classifiable firms, were at least 51 percent women-owned.

The National Women’s Business Council’s Necessity as a Driver of Women’s Entrepreneurship report distinguishes between two different motivating forces which push women to start their own businesses; they are opportunity-based entrepreneurship and necessity-based entrepreneurship.

In the former case, women are driven to entrepreneurship to take advantage of a market opportunity, while women in the latter case see starting a business as a last resort among other unfavorable options in the labor force. Women may find it necessary to start their own business not only to ensure their economic survival, but also when the labor market fails to meet their personal needs or accommodate their caregiving roles, such as a lack of paid leave, lack of affordable or subsidized child care or inflexible working arrangements.

Other factors that might push women towards entrepreneurship are related to obstacles of the “glass ceiling” women face in advancement. Some women stated a lack of promotional opportunities or recognition for women in their company, and dissatisfaction with the dominant masculine business culture and prioritization of the “old boys networks” as motivation for starting businesses of their own.

Declining Rate of Millennial Women Entrepreneurs

While the life of an entrepreneur is attractive to many millennials, and as much as 65 percent of believe they will become entrepreneurs in a 2016 report by Sage, the current of numbers of Millennials currently pursuing this career path is less than previous generations. Common career drivers among Millennials are independence, wanting to provide a public good and employee happiness. Self-employment can meet these goals, and then some, which is why many Millennials express interest in pursuing self-employment as a career path.

The Sage report, which include survey responses from 7400 Millennials from 16 different countries, shares Millennials’ reasons for wanting to start their own businesses. The most common motivator, at 40 percent, was the desire to be their own boss. Other incentives include wanting to be the master of their own identity, at 34 percent; wanting to make their innovative ideas a reality, at 24 percent; and wanting to make money, at 21 percent.

Despite this generation’s obvious interest in becoming tomorrow’s entrepreneurs, data on recent employment activity shows that less than 4 percent of Millennials in their 30s reported self-employment, according to the NWBC Millennial Women Entrepreneurs report. This is remarkably less than the self-employment rate of previous generations at this same age—5.5 percent of Generation X and 6.7 percent of Baby Boomers. This decline in the rate of Millennial entrepreneurs compared to previous generations is concerning because of the important effects new businesses have on job creation and economic growth in the country. The report mentions that about 20 percent of jobs are created by new establishments.

This decline in entrepreneurship among the young adults is linked partially to exorbitant student debt, reports a 2016 survey by Young Invincibles and Small Business Majority. It is common for young adults to take out loans as they pursue higher education, and the number of students who borrowed money for such purposes rose 89 percent between the years 2004 and 2014. During this same time, average debt balances grew by 77 percent.

A survey by Gallup and Purdue University reveals that student debt can influence millennials in delaying their entrepreneurial pursuits. Of those who graduated college with student loan debt, 19 percent said they have put off starting businesses of their own. If one’s student loan debt is more than $25,000, then the percentage of delayment increased to 25 percent. Because student loan debt has an inhibiting effect on the ability of the younger generation to start new enterprises, which are important for the economic growth and wellbeing of the nation, the report recommends an increase in programs that can assist recent graduates in managing their debt.

Studies show that there are gender differences in terms of student loan debt. For instance, research by the American Association of University Women (AAUW) indicates that millennial women face a higher burden of student loan debt compared to their male counterparts. While both genders share similar amounts of student loan debt, women tend to have lower personal income, thus it takes longer for them to pay it off. Intersecting factors that might contribute to a woman’s higher debt burden include college major, occupation, and work hours. Not to mention, women in the labor force are subject to a gender wage gap and “pink tax” that play a role in their annual income, and in how much money they are able to put aside toward paying off their student loans.

Studies show that there are gender differences in terms of student loan debt. For instance, research by the American Association of University Women (AAUW) indicates that millennial women face a higher burden of student loan debt compared to their male counterparts. While both genders share similar amounts of student loan debt, women tend to have lower personal income, thus it takes longer for them to pay it off. Intersecting factors that might contribute to a woman’s higher debt burden include college major, occupation, and work hours. Not to mention, women in the labor force are subject to a gender wage gap and “pink tax” that play a role in their annual income, and in how much money they are able to put aside toward paying off their student loans.

Current State of Women-Owned Businesses

Despite struggles millennial women might face in becoming future business owners, they can be inspired by the rising numbers of thriving and lucrative women-owned businesses that are taking up a large share of firms in the United States. It has been 30 years since the H.R. 5050: Women’s Business Ownership Act was passed, which was meant to address discriminatory practices that made it more difficult for women to start their own businesses. Some of its key legislative changes, such as eliminating the need for women to have a male co-signer for a business loan and creating the National Women’s Business Council (NWBC), led to an increase in the number and success of women-owned businesses.

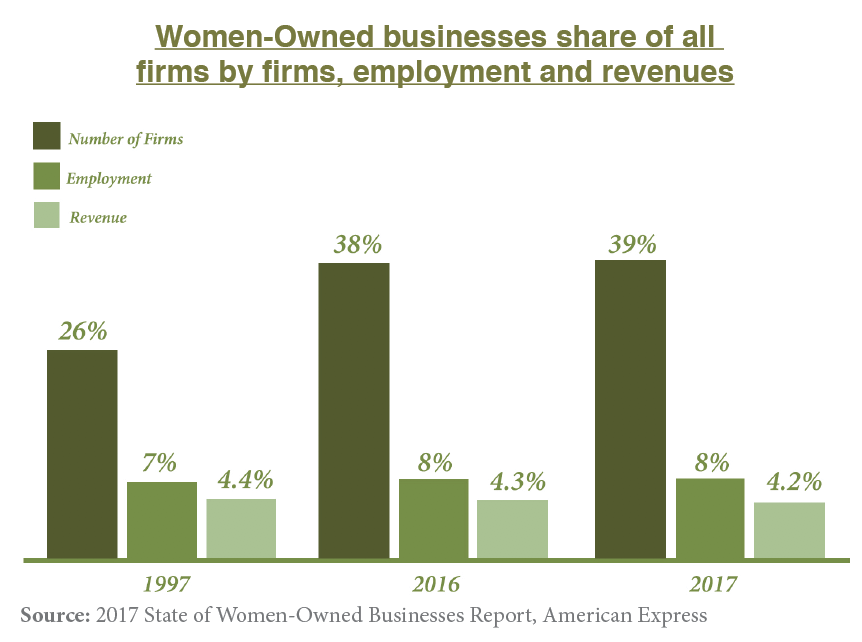

The 2017 State of Women-Owned Businesses Report, commissioned by American Express, states that the number, and revenue, of women-owned businesses in the United States has more than doubled in the last 20 years. There are 114 percent more women-owned businesses in the nation than there were two decades ago, and their revenue has increased by 103 percent by 1997. Moreover, the growth of women-owned businesses is taking place 2.5 times faster than the national average, with women starting an average of 849 new businesses per day.

Small businesses owned by minority women, especially women of color, have grown exponentially over the past 20 years. Firms owned by minority women comprise 46 percent of all women-owned firms, have over 2 million employees combined, and generate a total of $361 billion in revenue. According to the report, the number of firms owned by women of color grew by 467 percent during this time, which is over four times the rate of all women-owned businesses.

Women of color take the lead among minority women in the net number of women-owned businesses created per day and in the total number of firms in 2017. Below is a list of net new women-owned businesses per diem by race and/or ethnicity from 1997 to 2017, followed by list of the total number of women-owned firms, also by race and/or ethnicity. Both are recorded from the aforementioned report.

Net Number of Women-Owned Businesses

Per-Day by Race/Ethnicity (1997-2017)

• All minority owned: 609

• African American: 259

• Asian American: 104

• Latina: 227

• Native American/ Alaska Native: 15

• Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander: 4

• Non-minority: 240

Number of Estimated Women-Owned

Firms by Race/Ethnicity (2017)

• African American women-owned: 2.2 million

• Latina-owned: 2 million

• Asian American women-owned: 1 million

• Native American/Alaska Native women-owned: 161,500

• Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander women-owned: 34,200

The report reveals that women-owned businesses are seeing success all over the United States, and not just in the most populated states. While California, Florida, Texas, New York and Georgia have the most women-owned businesses, many rural states have an increased growth of enterprises owned by women.

The top five states where women-owned businesses increased their economic clout—including growth in number of firms, employment and revenues—between 1997 and 2017 are Nevada, District of Columbia, South Dakota, North Dakota and Georgia. Looking at only metropolitan areas, the places that had the most increased economic clout from 2002 to 2017 are Charlotte-Concord-Gataonia metro area, NC/SC; San Antonio, TX; Austin, TX; Indianapolis, IN; Riverside, CA; and Salt Lake City, UT.

At the industry level, the growth rate of women-owned businesses increased the most in construction, at 15 percent; arts, entertainment and recreation, at 12 percent; and other services, at another 12 percent. A majority of women entrepreneurs are starting businesses in the following three industries:

• 23 percent are in “other services,” including hair and nail salons and pet care services;

• 15 percent are in healthcare and social assistance, such as child daycare and home healthcare services; and

• 12 percent are in professional, scientific or technical services, which includes lawyers, accountants, architects, public relation firms and management consultants.

Women-owned businesses make significant contributions to the economy, and they can make an even greater impact if their share of employment and revenues—currently 8 percent and 4.2 percent, respectively—matched or exceeded their 39 percent share of firms. In addition, if the revenues of minority women-owned businesses matched the revenues generated by other women-owned businesses, the report predicts they could add $1.1 trillion in revenues and 3.8 million new jobs to the economy.

To see these predictions manifest in the future, there needs to be increased support in training programs in entrepreneurial, minority and women-owned certification, access to capital and greater advocacy of these issues. Current women entrepreneurs can also help by sharing their personal stories and advice for other women interested in starting their own businesses. By seeing women who have achieved their professional goals, future generations will be not only inspired but knowledgeable in the steps needed to make their dream a reality.

Ultra High Net Worth Women

Earlier this year, Forbes released the 2017 Billionaires List, which includes a staggering 2,043 individuals who rank as the richest in the world. Of these, only 227 were females, 56 of which created their own wealth. Although these numbers seem sparse, there is hope on the horizon for an increase of ultra-wealthy women. Just this year, the percentage increase in self-made women was higher than the increase in the number of billionaires overall. The population of ultra high net worth individuals, those with at least $30 million net worth, is still male-dominated with women accounting for only 12.8 percent, but women are increasing their share by means of entrepreneurship and generational wealth transfer.

According to the Wealth X World Ultra Wealth Report 2017, the number of men in the ultra wealthy category was 197,465, while women comprised 28, 985. Despite the fact that there are over 6 times the amount of men as women, the average net worth for both genders is relatively similar—$110 million for women and $120 million for men. With their average wealth of $110 million, the total wealth of ultra high net women was around a significant $3,190 billion.

The global report lists the top 30 cities with the highest population of ultra-high net worth individuals:

1. New York- Newark-Jersey City, NY-NJ-PA , with a UHNW population of 8,350;

2. Hong Kong, with 7,650;

3. Tokyo, with 6,040;

4. Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA, with 4,600;

5. London- Metro, with 3,630;

6. Paris-Metro, with 3,440;

7. Chicago-Naperville-Elgin, IL-IN-WI, with 3,110;

8. Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV, with 2,570;

9. Osaka-Kyoto, with 2,390; and

10. Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX, with 2,330.

U.S. cities comprised over half of the top 30 cities, and five rank in the top 10. Other cities that made it in the top 20 include Houston, San Francisco, Seattle and Atlanta.

The report includes an informative profile of the women who rank among the ultra-wealthy. Most of these women come from the United States, the United Kingdom and China, with a whopping 45 percent coming from the states. The average age of the ultra-wealthy women is 50, and 41 percent are younger. These ultra wealthy women are, on average, 12 years younger than the global ulta wealthy population.

While the Wealth X does not specify which cities have the most ultra high net worth women, other studies have listed cities where single wealthy women are likely to live. One study in particular created such a list by pulling U.S. Census Bureau data for metropolitan areas with over 1 million residents, such as the percentage of single women; the ratio of single women to single men; the percentage of women who make $100,000 or more a year; and the mean income of all women. The top 10 cities that ranked the highest in these categories included San Francisco, CA; Washington, DC; New York, NY; Boston, MA; Baltimore, MD; San Jose, CA; Philadelphia, PA; Hartford, CT; Providence, RI; and Los Angeles, CA. Not surprisingly, some of the country’s most wealthy single women, those bringing in a six-figure income or more, also live among other ultra-wealthy women.

Of women who gained their wealth, 45 percent were self-made, 19 percent were both self-made and inherited their wealth, and 36 percent inherited their wealth only. There is a clear gender disparity in terms of wealth source as women are 3 times more likely to have inherited their fortunes. According to the Wealth X report, 55 percent of ultra wealthy women received at least some of their fortunes through inheritance, compared to a third of men. However, there is a growing trend of wealth and business responsibilities transferring to younger female generations, which is likely to support the growth of women who generate their wealth through a mix of inheritance and self-made.

Ultra High Net Women and Entrepreneurship

Forbes reports that the percentage increase of self-made women was greater than the increase in the number of billionaires overall. In addition, the Wealth X World Ultra Wealth 2017 report reveals that women entrepreneurs will be important for increasing female representation among the ultra wealthy, since the wealth creation in the last two decades has been driven by self-made individuals.

To increase the number of women at the top, we should look up to those who have already made it there. Who are these women? How did they generate their fortunes, and how do we help position other women to do the same?

Entrepreneurship is the primary means by which women are generating their own wealth and adding to the ranks of the ultra-wealthy. There is a significant gender disparity in sources of self-made wealth. Sixty- eight percent of men, for instance, have made their own wealth compared to 34 percent of women.

However, statistics indicate that ultra high net women are three times more likely to inherit their wealth, and the report reveals 55 percent of ultra-wealthy women received some or all their fortunes through inheritance.

Some women are paving a middle road through partial inheritance and self-made wealth. This bracket may represent an increasing trend of families bestowing the family wealth and business onto the shoulders of young women. In addition to their inheritance, they earn a portion of their wealth by managing the family business.

Popular Industries for Ultra-Wealthy Women

A majority of the world’s richest women work in the following industries: non-profit and social organizations; finance; banking and investment; textiles; apparel and luxury goods; industrial conglomerates; and real estate.

There is a growing trend of single-family offices among self-made women. These offices ensure that they are in control of the way their wealth is used and managed. They commonly include a philanthropic goal, seeking to give back to local communities and society, such as children’s education, health and more. This report will expand more on family offices in the following section.

Entrepreneurship & Homeownership

Entrepreneurship is a tried-and-true method of establishing wealth that comes with other professional and personal benefits, including being your own boss, doing what you love and having flexible work hours.

Successful women entrepreneurs also benefit from financial independence, which opens doors to more opportunities. One of these is homeownership, and women buyers represent one of the fastest-growing segments in the housing market. Women are interested in buying their own home regardless of marital status, representing 13 percent of householders in the United States.

Owning a home is not only a profitable asset for wealth-building; it’s also a sanctuary where a woman can express her individuality, revel in her independence and maintain security.

Increase Investment in Women

In order to gain these benefits, women entrepreneurs need support to help their businesses thrive and raise their bottom line. Although women can achieve great heights with tenacity, strategic networking and negotiating skills, they also need adequate capital to drive their missions and goals.

Women entrepreneurs are facing a formidable gender gap in investment funding. Just last year, Fortune reports venture capitalists invested $58.2 billion in businesses founded by men, while only $1.46 billion went to women-owned businesses. This disparity is due to a combination of differences in the number of deals made and the average deal size, or the dollar amount, by gender.

Regarding the number of deals, although women-led businesses comprised 4.94 percent of venture capitalist deals in 2016—the highest percentage in the last ten years—only 359 companies received funding compared to 5,839 male-led companies. That is, companies run by men received 16 times more funding than those run by women.

In terms of deal size, Forbes reports that women-led companies received $4.5 million on average, a decrease from the prior year, although the percentage of deals that went to them increased. In contrast, companies led by men received fewer deals in 2016 but saw an increase in average deal size, at $10.9 million.

To improve this gap, investors must be informed about why investing in women is a good and profitable choice. For instance, businesses led by women entrepreneurs, a 2016 BNP Paribas Global Entrepreneur report reveals, generate 13 percent higher revenues than businesses led by their male counterparts.

When venture capitalists expand their view to include women-owned businesses, and offer a higher number of deals to them, a greater number of them will succeed. As a result, more women entrepreneurs will be given a chance to build their wealth towards financial independence. With continual progress and effort, we look forward to seeing more women added to the list of the ultra-wealthy.

Family Offices

There has been a considerable rise in the number of women entrepreneurs and they have been been starting many successful businesses and enterprises. Some factors that have contributed to their success, besides their own personal characteristics, hard work and tenacity, have been the growth of financing alternatives, marketplace trends, increased recognition of the capabilities of female workers, and companies understanding the necessity and efficacy of supporting women.

More women are taking up careers as venture capitalists, and some will leave their positions at successful companies to start their own businesses. Keeping in mind that women in the U.S. control $14 trillion in personal wealth—which the BMO Wealth Institute predicts will grow to $22 trillion by 2020—this trend has inspired interest in increasing the presence of women in family offices and wealth management.

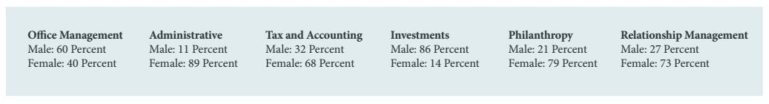

The 2016 FOX Family Office Compensation & Benefits Report, from Family Office Exchange and Grant Thornton, reveals that women comprise a majority of total employees of family offices, accounting for 59 percent. There is high female representation in management positions, with women comprising 89 percent of the Administrative field, 40 percent of Office Management and 14 percent of Investments. However, men outnumber women in executive positions in family offices at 60 percent. See below for gender representation in various levels of family office staff:

Many women are making their mark in the family offices industry, inspiring other future generations to follow in their footsteps. The Soho Loft’s global list of the “Top 10 Most Inspiring Women in Family Office and Wealth Management,” includes women from Singapore, London, Australia, South Africa and two women from New York. Their titles range from Managing Director and Client Advisor, to Chief Executive Officer and Founding Partner of some of the most successful family offices and investment management companies across the globe.

A family office is a private office that families of significant wealth have to manage their wealth and assets. Tasks of family offices range from key family assets and tax, accounting, property and estate management, to offering educational, professional and lifestyle services.

Family offices can either be single-family or multi-family. In the former, the offices are created to support the financial needs of one family that has at least $100 million or more worth of assets. In the latter, the family offices provide the same as one would in a single-family office but for more family groups. Multi-family offices are affordable for families with at least $50 million of assets each.

According to Bloomberg’s The Future of Family Offices report, in 2015, the total assets of ultra high net worth individuals amounted to $5.1 trillion. Family offices are becoming a popular way for these individuals to manage, protect and preserve their resources for future generations.

The 2016 EY Family Office Guide estimates that there are at least 10,000 single family offices across the globe, and half have been created in the last 15 years. In Bloomberg’s ranking of the richest family offices in the world, the top 10 listed family offices in the United States include 4 from New York, 2 from Chicago, 2 from Philadelphia, one from Minneapolis and one from Delaware.

The increase in wealthy, self-made women has run parallel to an increase in the amount of wealth controlled by family offices, according to Forbes. Women business owners primarily open family offices to ensure they are in control of their assets, and they often desire to use their wealth to help others by giving back to local communities and society.

The increase in wealthy, self-made women has run parallel to an increase in the amount of wealth controlled by family offices, according to Forbes. Women business owners primarily open family offices to ensure they are in control of their assets, and they often desire to use their wealth to help others by giving back to local communities and society.

While philanthropy might be an important objective for some family offices owned by wealthy women, the Bloomberg report lists other concerns of ultra wealthy high net individuals. The following includes the most prominent objectives of family office owned by either gender, ranked by importance:

• Intergenerational wealth management;

• Consolidating of accounting, tax and estate planning services;

• Family unit;

• Family education;

• Philanthropy; and

• Lifestyle enhancement (including concierge services).

According to the UBS Global Family Office Report 2017, a survey of 262 family offices in the United States with an average of $921 million in assets, 69 percent of family offices expect an intergenerational transfer of wealth in the next 15 years. This might explain why it is a top priority for ultra wealthy individuals. However, only a third of family offices expecting to transfer wealth to the next generation are prepared with written succession plans.

To ensure wealth preservation and growth across generations, it is important for family offices to have effective strategic plans for a smooth transfer. Such a transition needs the following elements, according to the UBS/Campden Wealth Global Family Office Report 2016:

• The next generation must be willing and able to manage the family wealth;

• The older generation needs to prepare to give up control;

• The family office must be flexible and trustworthy;

• The family itself should have functional relationships; and

• There should be practical governance structures.

Key Opportunities for Family Offices

Intergenerational Wealth Transfer

The increased necessity of intergenerational wealth transfer services as Baby Boomers retire is one of the key opportunities for family offices, according to the 2012 Global State of Family Offices Report. This is the time for family offices to assess what the next generation needs and establish programs that will help the next generation with future financial planning, as well as estate and tax planning solutions.

Coinciding with this opportunity is the trend of wealth and business responsibilities transferring to the younger female generation. This has led to an increase of the number of ultra high net worth women who have a combination of self-made and inherited wealth. We should see a continuing increase within the next 15 years as more family offices undergo this process of transferring wealth to younger family members.

Technological Advancement

As the world becomes more interconnected and globalized because of technology, family offices are presented with new opportunities for growth, as well as challenges in acclimating to change in the industry.

The report recommends that family offices globalize their investment portfolios by becoming more familiar with foreign markets and practices. Family offices will also benefit from offering more services to meet their clients’ needs in this technological advanced world, from physical security services to managing and maintaining their online profiles.

REITs

Another trend for Family Offices is investment in real estate. According to Ernst & Young Capital Advisors, LLC’s 2016 report, there are two general types of family offices that invest in real estate. The first type is usually a family that has accrued most of its wealth in real estate. These active investors are general partners who sometimes join with equity partners. Families who have generated their wealth outside of real estate, the second type, will allocate capital to this sector as a passive investor. They will invest in either funds, real estate investment trusts (REITs), or as a limited partner in a direct asset.

REITs are an indirect form of investment in real estate available in the public stock exchange or through private broker dealers and their distribution networks. Purchase of REIT units or shares offer liquidity and offer a variety of options for investors to best fit a family office’s unique needs.

Gender Lens Investment

As the global economy makes a recovery, a third opportunity foreseen for family offices is a shift from an emphasis on conservative investment strategies and wealth preservation to a focus on growth opportunities and alternative asset classes. The report recommends that family offices start evaluating the opportunities for investments into equities, real estate, private equities and others.

When considering diverse resources for increasing wealth, family offices should consider getting involved in the recent trend of gender lens investment. This type of investment focuses on women by evaluating opportunities based on how a certain investment will facilitate the following concerns:

• Women’s leadership;

• Women’s access to capital;

• Products and services that help women and girls;

• Equality in the workplace;

• Shareholder engagement and policy work; and

• Women investing their own resources.

If an investment satisfies at least one of these criteria, some wealth management companies believe it will have a positive impact on the economic opportunities and growth for women and girls.

Investment strategies with a focus on gender lens investing have been on the rise. According to Veris Wealth Partners, investment of this type has risen 41 percent in the past year, up to $910 million. In addition, the number of mandated publicly traded gender lens investment strategies has reached a total of 22, after 5 years of steady growth. This is an incredible increase from the years 1993 to 2012, when there were only 5 strategies for gender lens investing.

One reason for this shift might be related to the increased intergenerational wealth transfer mentioned above. The inheritances of the leading businessmen of the 20th century are being passed on to their wives, daughters and other millennial children. Veris also expects more women and Millennials to be wealth holders once these transfers occur, and these new wealthy individuals are interested in having their money invested towards important social and economic concerns, especially regarding gender equality, diversity and inclusion, and women’s economic empowerment.

Female Representation in the C-suite Corporations’ recent focus on diversity and inclusion with placing qualified women on boards has resulted in an increase of female representation at the executive level, but studies reveal that more work needs to be done to reach gender equality at all levels of employment.

McKinsey & Company’s Women in the Workplace 2017 report compiles data from 222 companies that employ more than 12 million people to show the status of female representation across the corporate pipeline and surveyed over 70,000 employees about their experiences regarding gender-related issues in the workplace. The report reveals that women, especially women of color, remain underrepresented in the corporate pipeline compared to men, and this disparity is not due to company attrition or women’s lack of interest in advancement. Moreover, commitment to gender diversity is harmed by company cultures that do not see current low rates of female representation as a problem, and worries that such efforts are disadvantages to men.

McKinsey & Company’s Women in the Workplace 2017 report compiles data from 222 companies that employ more than 12 million people to show the status of female representation across the corporate pipeline and surveyed over 70,000 employees about their experiences regarding gender-related issues in the workplace. The report reveals that women, especially women of color, remain underrepresented in the corporate pipeline compared to men, and this disparity is not due to company attrition or women’s lack of interest in advancement. Moreover, commitment to gender diversity is harmed by company cultures that do not see current low rates of female representation as a problem, and worries that such efforts are disadvantages to men.

The following breaks down representation down the corporate pipeline—from C-suite to entry level— by gender and race from the report. As shown above, the representation of women gets progressively smaller from entry level employment to the executive level, with each step of the ladder presenting further hurdles for women, especially when they pursue the jump from SVP to the C-suite. Currently, women make up 1 out 5 C-suite leaders, while women of color make up 1 out of 30.

Starting at entry level, women make up only 47 percent of hires despite comprising 52 percent of the U.S. population and 57 percent of college degree holders. The biggest gender gap occurs between entry level and management, as women are promoted at lower rates than their male counterparts. If corporations were to reach parity of gender representation at the entry level, then we would see the number of women at the SVP and C-levels more than double.

According to the report, women are 18 percent less likely to be promoted to manager than men. The rate of women’s representation decreases gradually from manager to VP. Women who aspire to rise in the ranks as top executives not only work hard but are likely to interact regularly with senior leaders. By the time these women become SVP, they, on average, hold only 21 percent of line roles. This decreases the chance for more women to reach the C-suite as most CEOs come from line roles.

It’s not entirely the case that this imparity in gender representation is due to factors such as women planning to leave their companies for other opportunities or lack of interest. Studies show that women are not leaving their companies at higher rates than their male peers, and few plan to leave the workforce to become stay-at-home mothers.

Of the employees surveyed in the report, 73 percent of women said they planned to stay with their company for the next 2 years. Of the 27 percent of women who said they plan to leave during this time frame, 72 percent expected to take a role at another company, and a slight 2 percent said they planned to leave to focus on family.

Furthermore, it’s not an issue of women not asking for the opportunity. Women of all races and ethnicities reported negotiating for a promotion and/or raise in the last two years at rates comparable to their male counterparts.

Female Representation by Industry

Female Representation by Industry

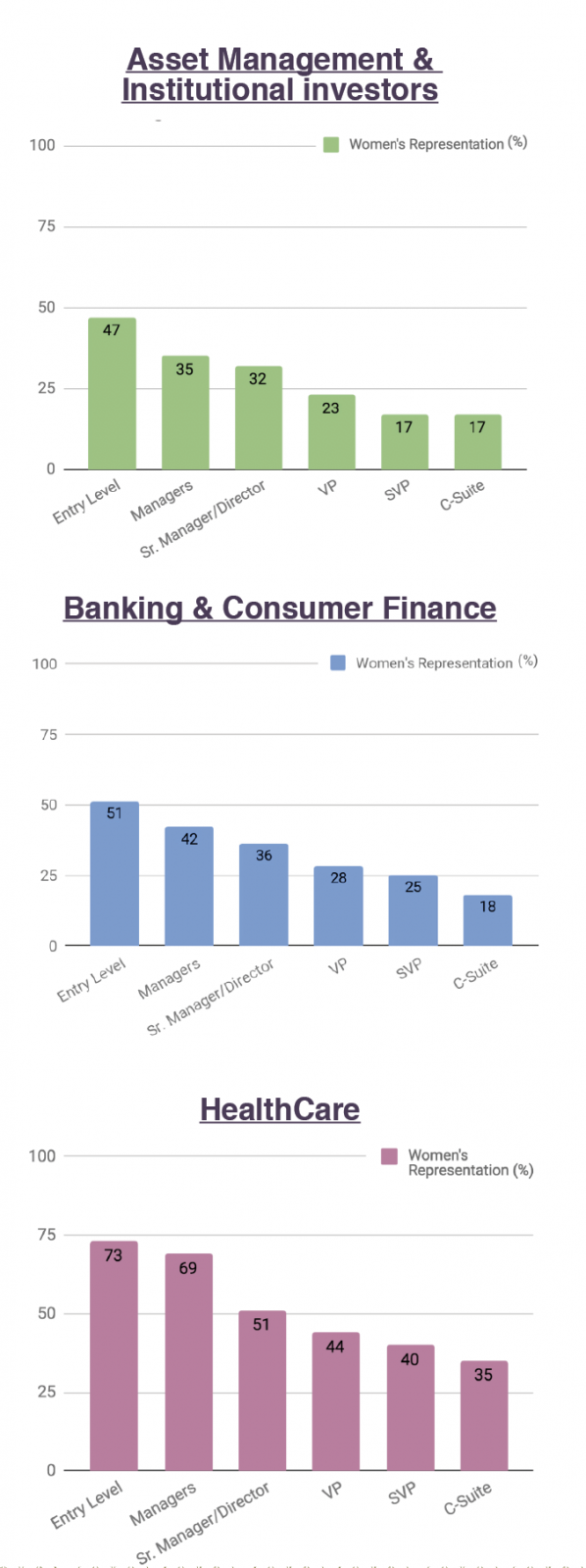

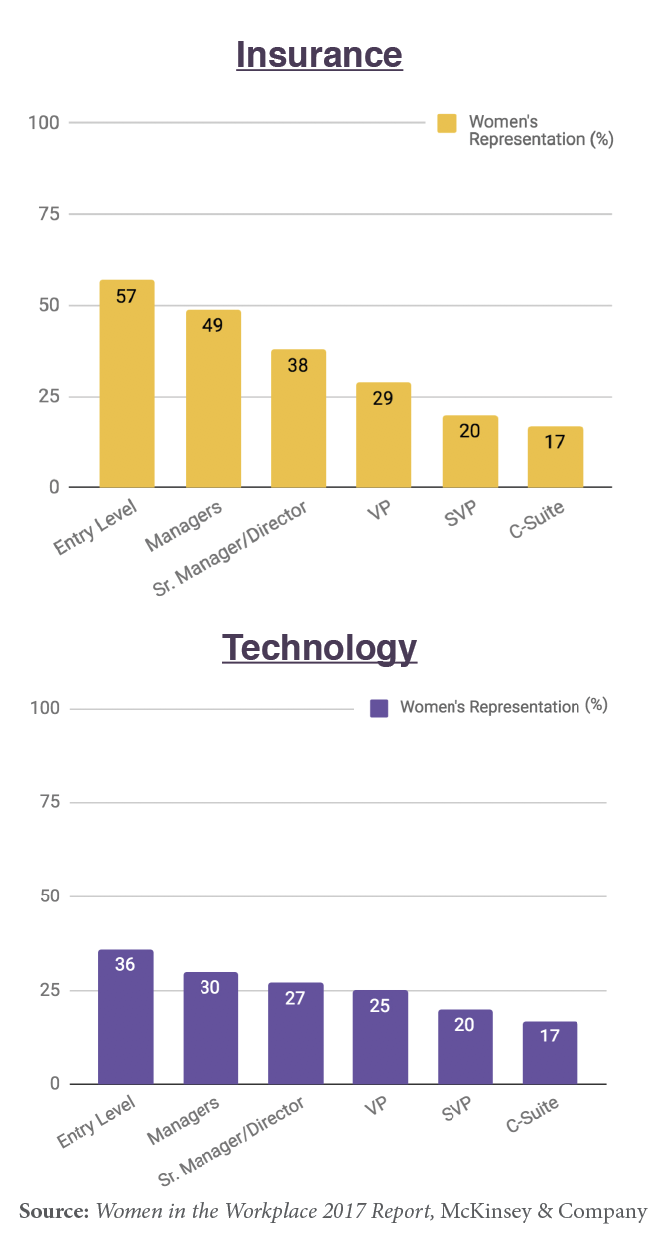

The Women in the Workplace 2017 report breaks down female representation in the corporate pipeline across various industries. In the following we include available data regarding industries related to the housing ecosystem— Asset Management & Institutional Investors, Banking & Consumer Finance, Healthcare, Insurance, Professional & Information Services (Legal), and Technology— to see whether women’s representation changes when we focus on different fields. Different industries have different pipelines; however, among these few industries, women’s representation is almost 50 percent or more at entry level and steadily decreases at middle management and the senior executive level.

Healthcare has the greatest representation of women at all employee levels, especially entry level at 73 percent. Despite the high presence of women in the healthcare industry, there is still a disparity of 38 percent between representation at entry level and the C-suite. In the Insurance industry, there is a 40 percent difference, the greatest of all industries highlighted above, between women’s representation at entry level and the C-suite.

Technology has a smaller difference, 19 percent, between women’s representation at entry level and the C-suite. At the same time, the industry has lower representation of women overall, most likely due to its difficulty in attracting women at entry level, who represent only 36 percent of entry-level employees.

The biggest hurdle for women’s advancement occurs in getting women to middle management as entry level employees; the percentage difference of female representation between these employment levels is the highest in Healthcare at 22 percent. Among these industries, the disparity in women’s representation between middle management and the C-suite is 12 percent or less. The Women in the Workplace 2017 report reveals that women who advance from middle management often receive advice from those at the top, have mentors, and interact with senior executives.

Women of Color Face Greatest Obstacles

Women of Color Face Greatest Obstacles

Women of color have the lowest representation at almost every level in the corporate pipeline, becoming increasingly sparse from entry level to the C-suite. These individuals experience unique obstacles in the workplace due to the intersection of unconscious biases related to race and gender. While only 1 out of 5 C-suite leaders is a woman, fewer than 1 in 30 is a woman of color. Women of color have a more arduous path towards the executive level, often receiving less support from their managers in career advancement and getting promotions at a lower rate than their peers. These disadvantages creates a poor perspective of the workplace and the opportunities available to them, but it does not diminish their dreams of having a seat at the table.

The Women in the Workplace 2017 report surveyed over 70,000 employees, and women of color reported their experiences in a corporate setting, from the support they receive from managers to whether they believe they have equal opportunity for advancement. The section below features responses women of color had to survey questions, along with the rate of women’s promotions and attrition for corporations.

The report provides the percentages of women of different races and ethnicities who agreed with statements regarding how much support they received from managers, such as whether

Managers advocated them for an opportunity:

• 31% of Black women agreed;

• 34% of Latina women;

• 40% of Asian women; and

• 41% of White women.

Managers defend them or their work:

• 28 percent of Black women agreed;

• 34 percent of Latina women agreed;

• 36 percent of Asian women agreed; and

• 40 percent of White women agreed.

Women employees were also asked about the equity of promotions and opportunities within their company, including whether

They have equal opportunity for growth as their peers:

• 48 percent of Black women agreed;

• 55 percent of Latina women;

• 55 percent of Asian women; and

• 59 percent of White women.

Managers provide advice to help advance them:

• 36 percent of Black women agreed;

• 39 percent of White women;

• 42 percent of Latina women; and

• 47 percent of Asian women.

Promotions are based on fair and objective criteria:

• 34 percent of Black women agreed;

• 39 percent of Asian women;

• 40 percent of Latina women; and

• 41 percent of White women.

The best opportunities go to most deserving employees:

• 29 percent of Black women agreed;

• 38 percent of Latina women;

• 40 percent of Asian women; and

• 40 percent of White women.

These numbers indicate that less than half of women of any race or ethnicity feel as if their managers advocate them for opportunities within the company, give them helpful advice on how to achieve growth, and are supportive of the hard work they do. A small proportion of women agree that management gives them stretch assignments, which give them a chance to show their capabilities and value to the company.

These numbers indicate that less than half of women of any race or ethnicity feel as if their managers advocate them for opportunities within the company, give them helpful advice on how to achieve growth, and are supportive of the hard work they do. A small proportion of women agree that management gives them stretch assignments, which give them a chance to show their capabilities and value to the company.

The report also reveals women’s attrition and promotion rates by race and ethnicity for 222 companies with over 12 million employees. The rate of promotion for Black women is 4.9 percent; 5.8 percent for Asian women; 6 percent for Latina women; and 7.4 percent for White women.

The rates of women’s attrition are slightly higher, with 18.2 percent for Black women; 16.5 percent for Latina women; 16.4 percent for Asian women; and 15.4 percent for White women.

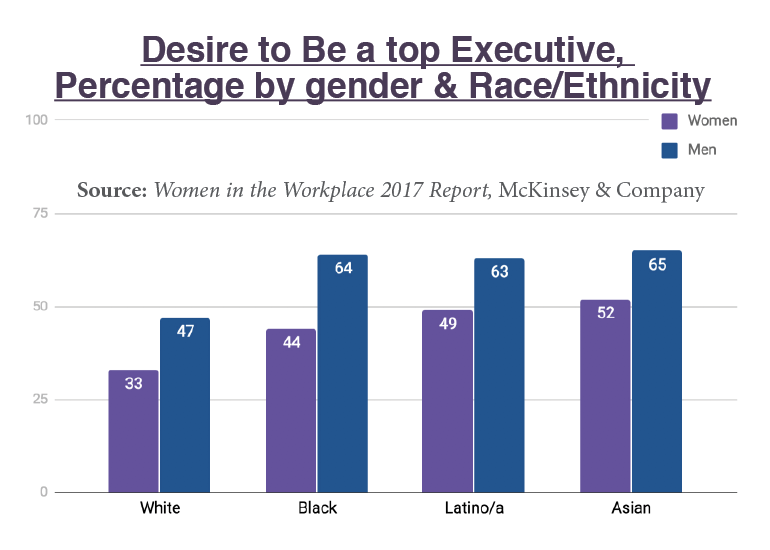

Not only do women of color face lower rates of promotion and attrition than White women, but they also experience less support from managers who could help mentor and guide them up the corporate ladder. Women of color, however, do not let these challenges hinder their dreams of becoming top level executives.

The percentage of these women who desire to reach the C-suite level even succeeds the percentage of White women with the same goal. Similarly, men of color also desire to be top executives at higher rates than White men. Women of color attempt to make these dreams come true with tenacity and hard work, and they are not afraid to ask for what they want. For instance, women of all races and ethnicities negotiate for either a promotion, or a raise, at the same rates as their male peers.

2020 Women on Boards

2020 Women on Boards

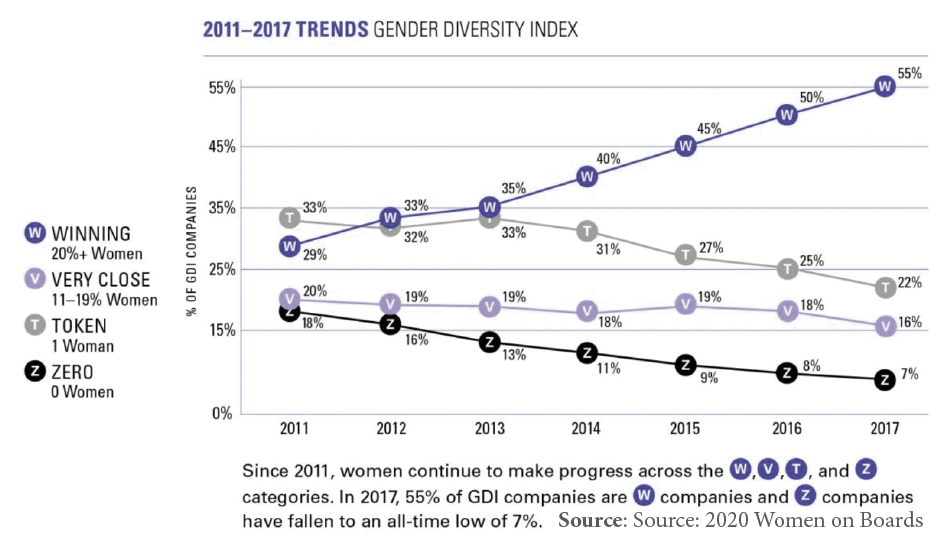

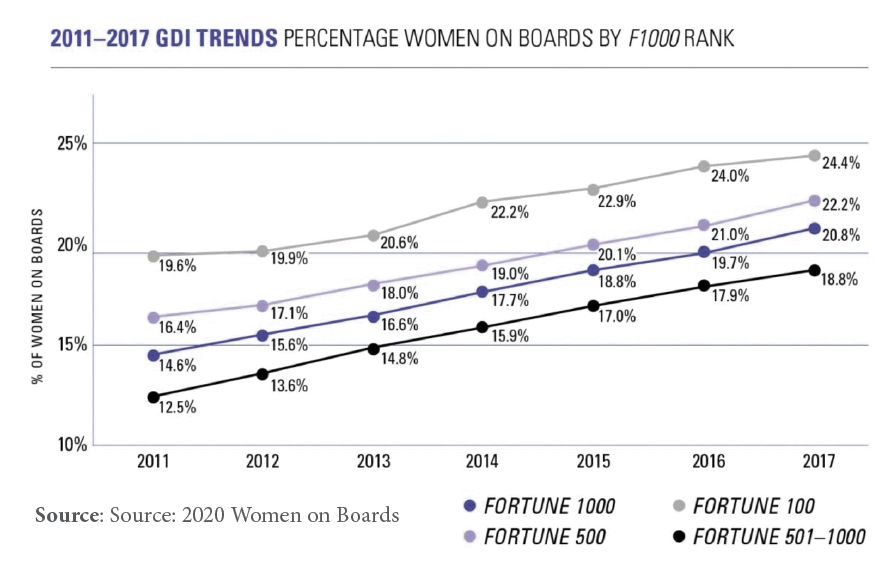

Organizations around the nation are bringing attention to the share of women at the senior executive level, including the board room. One of these is 2020 Women on Boards, a campaign that endeavors to increase the percentage on women on U.S. company boards to 20 percent by 2020. The campaign’s annual Gender Diversity Index provides updates on the representation of women on the boards of the nation’s most profitable companies, tracking those that are featured in the Fortune 1000 list.

This public index not only provides valuable information and highlights where progress has been made (and where it hasn’t), but also forces accountability from companies. It makes sure they are fulfilling the obligations of diversity and inclusion initiatives, and pressures them into action if they do not.

The latest report gives information on the status of women on boards for companies that have been tracked since appearing on the 2010 Fortune 1000 list, as well as those that made the list in 2017. There have been significant gains for women in the 801 active companies that have been tracked since 2010.

First, the 20 percent goal has been exceeded now that women hold 20.8 percent of board seats at these companies, an increase from 19.7 percent in 2016. Second, more than half of these companies are those which have 20 percent of board seats filled by women. In addition, the percentage of companies with no women on their boards decreased to 7 percent. A good portion of these companies, about 29 percent, have one or no women as board members. Since the campaign’s 2016 report, women have had a net gain of 67 board seats, while men have had a net loss of 183 seats.

The 2017 report also reveals methods these companies used to increase women’s representation on boards. Some companies added women by increasing the size of their boards—53 percent of those who hired women. This is a more expedient method of improving gender diversity at the top instead of waiting for seats to become available for replacement.

At the state level, 13 states exceed the 20 percent goal of women on boards, out of 24 that have the highest percentage of women’s representation. They include Connecticut; Wisconsin; California; Florida; Maryland; Massachusetts; Michigan; Minnesota; Missouri; New Jersey; New York; Ohio; and Washington.

The report also looks at female representation on boards by sector. In the 2017 Fortune 1000 list, 23 of the listed companies were in the Real Estate sector. Of these 23 companies, women represented 23.1 percent of board members, the highest percentage of all sectors compared. Financial Services and Technology, other industries related to the housing ecosystem, have a greater number of companies represented in the Forbes list—127 and 101, respectively. However, a greater number of companies does not correspond to a greater number of women on boards. The Financial Services companies have women represented at 22 percent, while women make up 18.8 percent of board members in the Technology companies.

The good news is that all the sectors represented in the chart above experienced an increase in women’s representation on boards. The companies, grouped by sector, which 2020 Women on Boards has monitored for their Gender Diversity Index (GDI), had more women on boards between 2016 to 2017. Real Estate entities had a collective increase of 3.1 percent; Financial Services, at 1.7 percent; Industrials, at 1.6 percent; Energy, at 1.3 percent; and Technology, at 0.3 percent. Overall, it appears Forbes 1000 companies in the Real Estate sector had the greatest percentage of women on boards in 2017, and those included in the GDI had the greatest increase in female representation from the previous year.

The good news is that all the sectors represented in the chart above experienced an increase in women’s representation on boards. The companies, grouped by sector, which 2020 Women on Boards has monitored for their Gender Diversity Index (GDI), had more women on boards between 2016 to 2017. Real Estate entities had a collective increase of 3.1 percent; Financial Services, at 1.7 percent; Industrials, at 1.6 percent; Energy, at 1.3 percent; and Technology, at 0.3 percent. Overall, it appears Forbes 1000 companies in the Real Estate sector had the greatest percentage of women on boards in 2017, and those included in the GDI had the greatest increase in female representation from the previous year.

Women in Real Estate

While a greater number of women in real estate are achieving position on boards at a national level, women still trail behind men in obtaining leadership positions in some states, including California. According to a the California Association of REALTORS (CAR) Membership Survey conducted in 2017, including nearly 1,600 REALTORS, women comprise only a third of leadership positions in brokerage firms with more than 100 agents even though they make up 57 percent of REALTORS in the state. In addition, the survey reveals that women have led 29 percent of the top 500 firms across the country for the past five years.

A large portion of professionals in the real estate industry do not think gender discrimination is the main cause of the gap in leadership positions. In a 2016 Inman News Special Report titled “Why Aren’t More Women in Real Estate Leadership?”, 71 percent of both men and women believed both genders were given the same opportunities and 60 percent said that gender did not play a role in missing out on a raise, promotion, or key assignment.

While an evident gender gap in leadership in broker-owner and teams shows that women are missing out on these opportunities, CAR’s report suggests that this discrepancy might be due to women opting out of the corporate ladder to start their own brokerages. CAR’s interviews with 25 case studies reveal that some women are choosing to opt out of large brokerage models and create their own businesses for the following reasons:

Desire to create a company that reflects their unique vision and values

Existing brokerage models fail to meet their needs or provide them with insufficient freedom

Accommodate their multiple roles as wife, mother, leader, etc.

Child care needs

These reasons indicate that one of the obstacles women in real estate face is achieving a work-life balance so that they can succeed in a career they love while maintaining their relationships and meeting their obligations in the domestic sphere. Women professionals also desire the freedom that comes with being their own boss and creating a company that reflects their values and individuality. It would be optimal if both the corporate sector and entrepreneurship could help women meet their needs, but the latter option currently seems to do a better job of it.

Gender Diversity Across the Globe

Mercer’s When Women Thrive 2016 report highlights the state of gender equality in the workforce at a global scale—with research covering 583 companies, 3.2 million employees and 42 countries— and suggests strategies that can help increase the representation of women at various employment levels.

According to the World Economic Forum’s 2015 Global Gender Gap report, we are 118 years away from witnessing the close of the gender gap for labor market opportunity, education, health and political clout. Today, the Mercer report reveals that women make up only 35 percent of an average companies workforce, at the professional level and beyond. Women in the labor force globally comprise 33 percent of managers, 26 percent of senior managers and 20 percent of executives. Many companies have made an effort to increase female representation among their employees, especially at the executive level, through their practices and initiatives. The recent focus on hiring more women has been partially driven by increased regulation and media attention on diversity and inclusion in the workforce.

While companies have exhibited a concerted effort at hiring more women at top level employment, the report predicts that current rates of hiring, promotion and retention are not enough to obtain gender equality in the long run. There are two main reasons for this. First, statistical improvements in female representation are the result of ad hoc solutions of hiring more women at the executive level, and not of systematic practices throughout a company. Second, improvements in female representation and hiring practices at executive levels are not mirrored in lower levels of employment. In other words, reaching true equity in gender representation requires a joint change in all levels of employment, from entry level to the board room.

The report provides an overview of gender equality in the workplace across the globe to see where women are thriving, and what these regions are doing to help them thrive. The continental regions included in their analysis are Asia, Europe, Latin America, the US and Canada, and Australia and New Zealand.

Asia

Mercer projects that Asia will have the lowest representation of women by 2025 at only 28 percent at the professional level and above. Organizations in this area are less likely to be focused on gender diversity than the other regions studied. In effect, this means they are less likely to engage middle management to enforce gender diversity practices or engage the male population among their employees. They are also less likely to adopt thorough pay equity processes, or review performance ratings by gender to check for any stark disparities.

Europe

Europe has seen improvement in female representation at top levels of employment, but the report warns that this will not extend into further improvement at the professional level and above over the next decade. In 2025, women are likely to make up 37 percent of employees at the professional level—the same as today.

Women are hired at almost double the rate of men for top positions at European organizations. This is likely impacted by quotas, regulations and pressure from the media for gender diversity in the workplace. However, such targeted attempts to increase women at the top are only a band-aid solution for a problem that requires policies and practices throughout an organization’s structure, especially since senior women are more likely to leave a company.

Latin America

In Latin America, women comprise 17 percent of executives, and, if current hiring, promotion and retention rates are maintained, female representation is likely to grow to 44 percent by 2025. Of all the regions included in the report, Latin America is on track to achieving gender parity at the professional level and above within the next ten years.

Among organizations, women are more likely than men to be promoted at entry level, and twice as likely to be promoted at the senior management level. In addition to high promotion rates for women, 51 percent of organizations in Latin America are driving middle management engagement in diversity and inclusion efforts, and 48 percent are working toward equal representation in P&L and functional job positions.

US & Canada

Organizations in North America have a greater percentage of women in the mid- and senior-level workforce than in any other region, and they have also seen improvements in promotion and hiring rates of women at the executive level in the past year. US and Canada are also ahead regarding retirement and savings education programs offered by gender, although only 14 percent of organizations customize these programs.

Despite these achievements, organizations in this region have also utilized quick fixes in hiring more women in senior-level positions. Without structural practices and policies to increase gender representation at all levels of employment, the report predicts that there will not be enough talent flow to grow women’s representation over the next decade.

Implementing such policies and practices to increase gender diversity requires the engagement of middle management. However, without proper training, some managers do not feel they are qualified to run these programs effectively. Currently, less than 25 percent of organizations agree that managers are provided adequate training to manage leave and flexibility programs or report equal representation.

Australia & New Zealand

In Australia and New Zealand, organizations have lower hiring and retention rates of women at the executive level, compared to their male counterparts. Women currently make up 17 percent of executives and 33 percent of those at the professional level and above. Organizations in this region rank second lowest of those studied in terms of rates of women’s representation. If this continues, women will only make up a third of top jobs in 2025.

Companies in Australia and New Zealand are more likely than other regions to review performance ratings by gender and manage leave and flexibility programs for their employees.

Characteristics of Effective Gender Strategies

The Mercer report offers strategies to advance women in the workplace at the individual and organizational level. These suggestions are combined to form Mercer’s 6 P’s of an Effective Gender Strategy.

Individual Level

Have Passion to Drive Diversity

Passionate leaders are needed to drive diversity within an organization. Currently, of the organizations studied in the report, only 52 percent believe their board members are engaged in D&I efforts, and just 39 percent believe there middle managers are engaged.

Empirical evidence shows that organizations with engaged leaders in D&I have more women at top positions, and they hire, promote, and retain women at higher rates than men. Engaged leaders not only set mandates but also drive change with transparent communication with employees, but also demonstrate behavior that shows a commitment to diversity.

Make it a Personal Priority

Diversity can be achieved when women and men work together to ensure equal opportunity within their organizations. According to the report, women thrive when men are engaged in D&I efforts. Gender diversity needs to adopted by all employees because having a diverse workforce helps the entire company succeed.

Only 38 percent of organizations said that their male employees are engaged in D&I activities. More transparent conversation might be needed to communicate that gender diversity is beneficial for both women and men, in terms of family economics and more opportunities and flexibility.

Show Perseverance Over Time

Last but not least, an effective gender strategy requires individuals to persevere in creating opportunities for women for the long term. Recently, organizations have been focused on increasing the number of women at the top, which is important since women only comprise 20 percent at the executive level, but growing women’s representation in the workforce at the professional level and above requires more integrated practices and policies.

If we do not focus on women’s representation down the pipeline, from the C-suite to entry level positions, then women will only makeup 40 percent of the professional workforce by 2025. This means not only adding women’s diverse talent to the top, but also giving opportunity for more women to show their worth as they climb the ladder.

Men are continually hired and promoted from mid-level positions at higher rates than women, even though women have had improved hiring rates, compared to men, at senior levels. Building a talent pipeline for women to succeed within an organization is the surest way to make gender equality a reality in the future.

Organizational Level

Rely on Proof Before Jumping to Solutions

When creating strategic plans for issues of gender inequality in the workforce, it’s important to do some external and internal research on which practices are helping and which are not. Look at public research and data on successful D&I practices and determine the most salient characteristics among them. Also, seek feedback from within your organization from managers and employees about the effectiveness of implemented practices. Having an insider perspective is invaluable for understanding what is working and where the organization can improve.

One important means of ensuring gender equality, according to Mercer’s report, is having actively-managed leave and flexibility programs for employees. When both men and women have access to leave programs, organizations gain higher female representation in their workforce. As of now, 29 percent of organizations report they supply their managers with training for administering the following processes: supporting employees as they go through maternity or paternity leave, helping employees in return to work, and challenging unconscious biases that might influence rewards and promotion decisions affected by an employee’s leave.

Another means of increasing female representation is for organizations to rethink the traditional job design and leverage the unique skills and strengths women have relative to men in high-impact roles. There is a preconceived notion that men possess the natural competency to be successful leaders, but women are just as capable, and arguable more so, of being influential and effective leaders.

In a 360-degree feedback instrument, conducted by Business Insider, measuring competencies of about 16,000 men and women leaders, women scored higher than men in 12 out of 16 competencies. These include not only nurturing competencies—such as developing, motivating and inspiring others; relationship building; collaboration; and teamwork —but also the ability to take initiative, display integrity and honesty, and drive for results. The competencies where men scored higher include developing strategic perspective and professional, or technical, expertise.

All of these competencies are diverse skills that individuals need to be great leaders that drive an organization’s success through the changing economy, and both men and women possess the necessary skills to take on this role.

Install Regular, Robust Processes to Ensure Equity

According to Mercer’s report, women are able to thrive in the workforce when organizations have a strong pay equity process, as they are more likely to have greater female representation when they also have a team dedicated to gender equality. Of those surveyed in the report, only 35 percent of organizations have a robust pay equity analysis process with a statistical approach.

To ensure equity in payroll, organizations should consider implementing processes based on pay data and statistical analysis. These processes should also be supplemented with remediation protocols that can identify and address any risks.

Another method for ensuring equity is to have fair processes for promotions and performance management with a gender lens. According to the report, 30 percent of organizations conduct routine performance ratings by gender to search for any disparities related to inequities in opportunities for men and women. Organizations that actively review their processes for any incongruencies between gender—a responsibility assigned to both Human Resources and the company itself—are more likely to have greater female representation as they make sure women have the same opportunities as their male counterparts to grow.

Implement and Support Critical Programs

It is crucial for organizations to assist a diverse workforce with programs that meet their unique health and financial needs, which vary between men and women. Only 22 percent of the organizations included in the report stated that they run analyses to identify gender-specific health needs and education.

Women might also need specialized programs to meet their unique financial situations to help them succeed in the organization. Compared to men, women face the following obstacles in maintaining financial independence and stability: (1) they tend to have lower-paying jobs than men; (2) they have more gaps in services; and (3) women, on average, live longer than men. According to Wells Fargo’s Women and Investing: Building and Strength report, women tend to outlive men by five years.

Because they tend to have longer lifespans, women need retirement funds to last longer. In addition, studies have shown women to be more risk-averse investors, which affects overall returns. Currently less than 10 percent of organizations offer retirement plans that meet men and women’s distinct needs, or that monitor the savings and investment choices of each.

Obstacles in Policy Solutions: Gender Quotas

Setting gender quotas is one way some organizations across the globe are trying to increase female representation at the executive level and in boards. In an article published in the Harvard Business Review, MargaretheWiersema, who holds Dean’s Professorship in Strategic Management at The Paul Merage School of Business, University of California, Irvine, and Marie Louise Mors, Professor of Strategic and International Management at the Copenhagen Business School (CBS), reveal perception of gender quotas from over 60 male and female directors in the U.S. and Europe, and how these views can negatively affect success in achieving these quotas.

Over ten years ago, businesses in Europe adopted measures to increase gender diversity in their corporate boards, with either quotas or voluntary goals. Their ultimate goal was to increase female representation from 25 percent to 40 percent. Norway was the first European country to adopt a gender quota for hiring female board members in 2004, and other countries followed suit, including Iceland, France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, and the UK. As of 2016, only Norway and Iceland have successfully reached their quota.

Australia, Denmark, and the U.S. are among Western-developed countries where neither voluntary goals nor quotas have been set to increase female representation in corporate boards. In the U.S., female representation in the boardrooms of the S&P 500—at 18.7 percent— has not changed significantly in the last decade, and continues to be lower than most of Europe.

Although gender quotas have been successfully adopted and achieved in these aforementioned countries, there has been considerable resistance among both male and female board directors, especially in countries that have yet to implement any gender diversity measures. These board directors voice a range of doubts about the necessity and efficacy of gender quotas, from remarks that it would result to the hiring of unqualified women into boards to concerns that it demeans women.

When Danish Prime Minister HelleThorning-Schmidt introduced the idea of placing gender quotas in Denmark, it faced push-back from the Minister of Equality and Vice Director of the Danish Confederation of Industries, both of whom are women, who stated such quotas would “lead to selection of unqualified women or selection purely on gender.” This sentiment encapsulates the common worry, though unfounded, that gender quotas would lead to the hiring of less qualified directors.

In the U.S., both male and female board directors held similar views. In the article, one male director stated, “I think it is dumb and destructive—demeaning to people who are only on the board because they are in a specific category.” A female director believed that such quotas would demean women who are hired into boards as a result of the measure: “No one wants to be a second-class citizen.”

Other male directors in the U.S. believed that corporations were displaying diversity awareness in their hiring processes and formal quotas were not needed. While admitting that progress has been sluggish, businesses have gender diversity in mind when they search for board members, taking into consideration candidates of both genders. Their main priority, they stated, is hiring the most ‘qualified’ and ‘strong’ directors.

An open mindset while reviewing candidates is good to have, especially since the board selection process predominantly occurs within social networks, but the numbers show it has not been enough for increasing female representation at the top level. As one board director states, “Boards need to look in the mirror. Does the composition make sense? Women represent 50% of the workforce, 30% of managers and 4% of top leaders? This is not a meritocracy…the numbers don’t add up.”

In order for significant change to occur, countries might have to adopt a more rigorous and formal approach to the problem of gender diversity and female representation at the board level. As one director notes, gender quotas have resulted in not only greater diversity but also a more professional approach to the board selection process that is based more on merit than whom one knows. However, these quotas will only be successful if they are embraced by the entire company, especially board directors themselves, into one of its core tenets. Gender diversity should not be seen as an end goal, but as an integral part of a company’s practices and functions.

Trends & Analysis

The following are some of the key areas of focus in terms of gender equality for women professionals in the workforce.

Focus on Female Representation at All Levels of Employment

Many sources that analyze female representation in the workforce and present methods for increasing gender diversity agree that our focus needs to be at all levels on employment, not just at the top. Recent efforts to increase gender diversity have placed priority on hiring more women at executive level positions. Although this is an important aspect in effecting change, it is not enough to guarantee gender diversity in the long term.

As Mercer’s When Women Thrive report explains, growing women’s representation in the workforce at the professional level and above requires more integrated practices and policies. If we do not focus on women’s representation down the pipeline, from the C-suite to entry level positions, women will only makeup 40 percent of the professional workforce within the next decade.

Women of Color Face Greatest Obstacles in Advancement

While the number of businesses owned by women of color have grown exponentially over the past 20 years, women of color face greater obstacles in terms of career advancement, and have unique experiences due to the intersection of race and gender.

McKinsey & Company’s Women in the Workplace 2017 report reveals that women of color remain significantly underrepresented in the corporate pipeline compared to men, and this disparity is not due to company attrition or women’s lack of interest in advancement.

Currently, women make up 1 out 5 C-suite leaders, while women of color make up 1 out of 30. Women of color have a more arduous path towards the executive level, often receiving less support from their managers in career advancement and getting promotions at a lower rate than their peers. These disadvantages create a poor perspective of the workplace and the opportunities available to them, but it does not diminish their dreams of having a seat at the table.

Company Culture Affects Effectiveness of D&I Initiatives

As this report shows, D&I initiatives are only effective if they are adopted as part of a company’s practices and ethos. There can be disagreement within an organization about the necessity and effectiveness of these efforts, from entry-level to the executive level, which should be discussed in an open, encouraging environment. If a company’s top executive and managers do not make D&I a priority, then it cannot be expected that other employees will.

D&I initiatives can effect change when all genders and employment levels work together to ensure equal opportunity within their organizations. As Mercer’s When Women Thrive report states, women thrive when men are engaged in D&I efforts. Gender diversity needs to adopted by all employees because having a diverse workforce helps the entire company succeed.

Main Characteristics of Effective Gender Diversity Strategies

Effective gender strategies are those that take place at the individual and organizational level. This report highlights some of the key characteristics of effective practices at increasing female representation at all professional employment levels, as stipulated in Mercer’s report.

At the individual level, an effective strategy at increasing diversity needs to be led by passionate leaders who drive change through open communication and exemplary behavior; adopted as a personal commitment by both employers and employees; and created to ensure perseverance over time by focusing on more than just hiring more women at the top.

At the organizational level, organizations should first conduct research outside and within their company to figure out which practices are creating change and which efforts need to be improved. This might involve creating better leave and flexibility programs for their employees, reconfiguring leadership roles that complement women’s unique competencies, and training their managers to effectively administer leave and return-to-work processes.

Second, women are able to thrive in the workforce when organizations have a strong pay equity process, as they are more likely to have greater female representation when they also have a team dedicated to gender equality. Methods organizations should consider for ensuring pay equity include adopting processes based on pay data and statistical analysis, supplemented with remediation protocols, and implementing fair promotions and performance management with a gender lens.

Third, it is crucial for organizations to assist a diverse workforce with programs that meet their unique health and financial needs, which vary between men and women. Compared to men, women tend to have lower-paying jobs, have more gaps in terms of provided services, and live longer. Companies should take into account the various obstacles women face in achieving economic growth when implementing programs to help them succeed at the personal and professional level.

In conclusion, an overriding theme of these various studies is that an effective method of increasing women’s representation will require more than meeting quotas. Placing experienced women on boards and appointing them to senior executive positions is important as we need more diverse voices at the table where major decisions are made. However, for women professionals to be perceived as more than just token hires, there needs to be a culture shift in companies that embraces diversity and inclusion. In addition, more women need to be hired at entry and management levels, and given opportunities to rise through the ranks, from management to the C-suite. Once current executive women leave their positions, we need to create a pathway for other women to take their place—a place they earn by merit, and through the visible hard work they did to get there.

Login

Login