Executive Summary

Executive Summary

The NAWRB: Women in the Housing Ecosystem Report is published by the Women in the Housing & Real Estate Ecosystem (NAWRB), a leading voice for women in the housing ecosystem. This report raises awareness of women entrepreneurs’ successes and obstacles, and analyzes the ramifications of workplace gender imbalances on women’s homeownership.

These listed factors impact women’s ability to reach economic independence, and the gender disparities within each play a tremendous role preventing women from achieving homeownership:

• Employment and income

• Entrepreneurship

• Education

• Women’s poverty

• Discrimination in mortgage lending

• Family and community support

In addition, women face the following barriers as professionals in the housing ecosystem:

• Bias against female advancement

• Gender income gap

• Lack of mentorship opportunities

Women in the Housing Ecosystem

Women’s buying power is certainly affected by their incomes and employment opportunities, and women who work in the housing ecosystem face unique challenges in attaining advancement, thus higher wages.

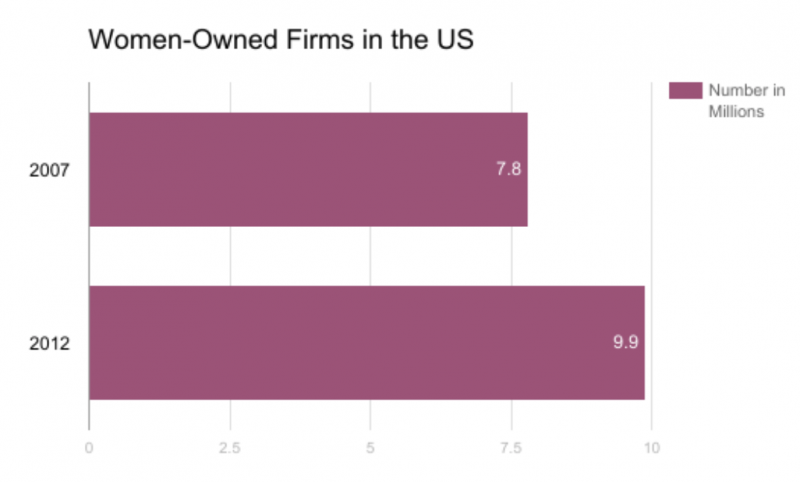

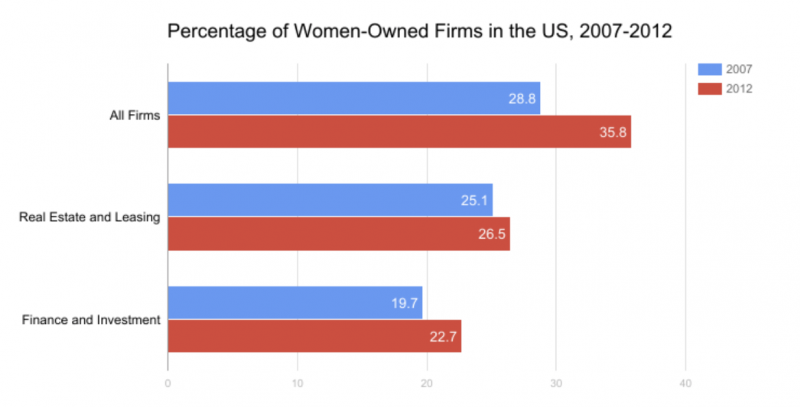

Entrepreneurship is a powerful tool for the creation of wealth and upward mobility, and many women are building their careers as entrepreneurs and business owners. According to the 2012 Survey of Business Owners (SBO), there are 9.9 million women-owned firms in the United States, rising 26.8 percent from 7.8 million in 2007.

This report includes information on women-business owners in commercial real estate and the finance industry, in the United States and in California. Current data reveals disparities among women and minorities in percentages of business owners, executive and management positions, and in a pervasive gender income gap. In commercial real estate, for example, there is an approximate 23 percent income gap.

Trends and Projections

Five-Year Trend in Women’s Homeownership

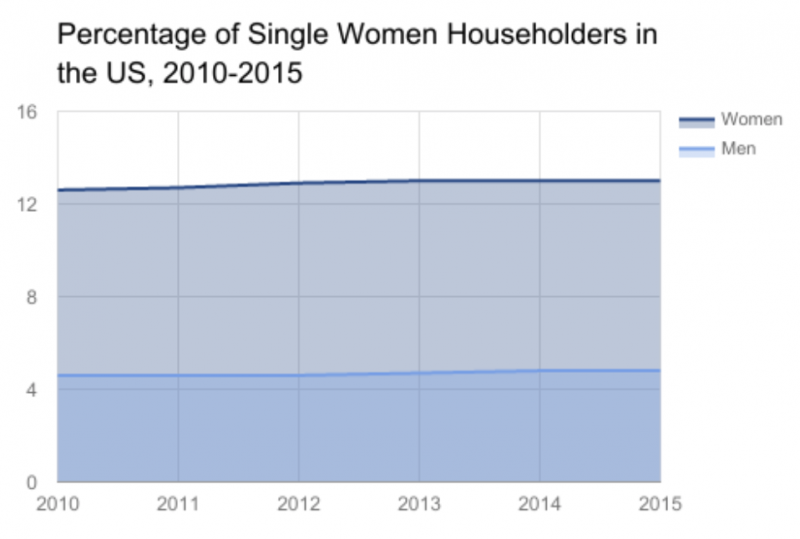

• The percentage of single women homeowners has increased about 0.4 percent from 2010 to 2015. The percentage of female householders has remained at 13 percent from 2013-2015.

➢ This plateau may continue into 2017, but we should hopefully see an increase, even if under one percent, in 2020, especially as more Millennials will become first-time homebuyers.

Growth of Women-Owned Businesses in the United States

• From 2007 to 2012, the percentage of women-owned businesses has increased about 7 percent for all firm types; 2 percent for real estate and leasing firms; and 3 percent for finance and investment firms.

➢ In upcoming data from the 2017 SBO, released next year, we will hopefully see a continuing upward trend of women-owned businesses.

➢ A more concerted effort will have to be directed at increasing the number of women in C-suite positions, especially in industries such as finance where women’s representation is decreasing at the senior management level, according to a 2013 GAO report.

Women’s Homeownership

The most recent data on women’s homeownership reveals that women’s desire for homeownership is present and growing. According to 2014 Census Bureau data, there are over 18 million female homeowners in the U.S. Ten million live alone, 6.7 million live with relatives without a husband present and 1.3 million live in two-or-more-person households.

Women are becoming more independent, focusing on attaining higher degrees and establishing their careers and pushing back traditional gender roles, such as becoming wives and mothers, later in age. Women are entering marriage at age 27, U.S. Census data shows, compared to 21.5 years in 1940.

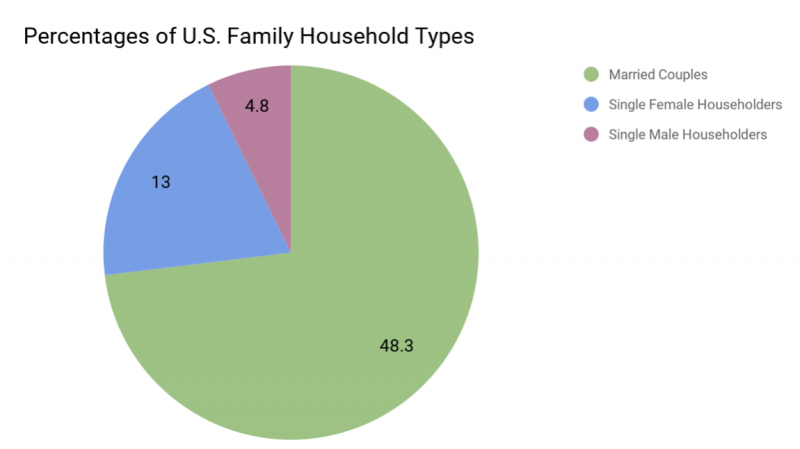

Not surprisingly, some financially independent women are making the decision to buy their own homes regardless of marital status. Of the nation’s current occupied housing units, a number exceeding 116 million, single women make up 13 percent of family households; in contrast, single men homeowners make up only 4.8 percent.

We will see these numbers grow as pay parity and barriers to women’s economic independence are addressed; as of now, affordability is one of the key barriers in women’s homeownership.

Despite comprising a larger group, single women homeowners face disadvantages compared to single men homeowners: In the U.S.—principally due to women’s lower buying power—homes owned by single men are worth 10 percent more; and, as a result of their higher worth, single men’s homes appreciate 16 percent faster than homes owned by single women.

Proposed Solutions

To improve women’s buying power compared to men’s, and improve women’s homeownership as a result, we must encourage the inclusion of women in male-dominated, higher-paying occupations, which are predominantly STEM fields.

This process starts with education and continues into employment. To cultivate today’s young women into tomorrow’s scientists, engineers, mathematicians, chief executive officers, entrepreneurs, and more, we have to inspire them to attain STEM degrees in college.

As working professionals in the labor force, women need to be given the tools for vertical growth. First, company cultures need to address bias against female advancement at all levels of employment, with a starting point at corporate management.

Second, companies have to implement mentorship programs within their organization geared towards their female employees. Having a mentor or sponsor within their company is an invaluable asset for women’s advancement from middle management to the C-suite; in contrast, not having access to one can harm women’s motivation for advancement.

Part One: Women’s Workforce

Homeownership is a pivotal part of the American Dream, if not the American Dream itself. Owning a home gives a person freedom, confidence, and a place to call their very own. As women progress in the workforce and build careers, it is crucial to fortify their growth with a strong economic foundation. Homeownership is important for women, whether single or married, because it provides the financial security to safeguard their professional progress and paves the way for future generations of women.

For some women, however, homeownership seems such a farfetched idea that it remains only a dream; some women who live in poverty may not even consider something that seems impossible to them. This needs to change. We need to show these women that the impossible is possible, and address the barriers which prevent them from becoming homeowners.

This report raises awareness of women entrepreneurs’ successes and obstacles, and analyzes the ramifications of workplace gender imbalances on women’s homeownership.

To further examine the connection between poverty and women’s lack of homeownership, illustrating the pervasive manner in which these two factors intertwine to help prevent women’s progress, the report shines a light on the power of homeownership to cement one’s economic foundation and professional success.

Upon analysis of notable reports and studies, we have collected data on housing, education, business, entrepreneurship, and employment as they relate to women and gender equality. These factors all impact women’s ability to reach economic independence, and the gender disparities within each play a tremendous role preventing women from achieving homeownership. Women also face barriers such as bias against female advancement and a pervasive gender income gap as professionals in the housing ecosystem.

General Stats on Women

Women have made significant strides in attaining independence and increasing their purchasing power by gaining higher levels of education, earning higher-paying jobs, entering career paths previously dominated by men and starting their own businesses. As a result, they are focusing on financial independence and challenging traditional gender roles by marrying and having children at a later age.

The following statistics reveal some of women’s advancements in recent years.

Women in the Labor Force

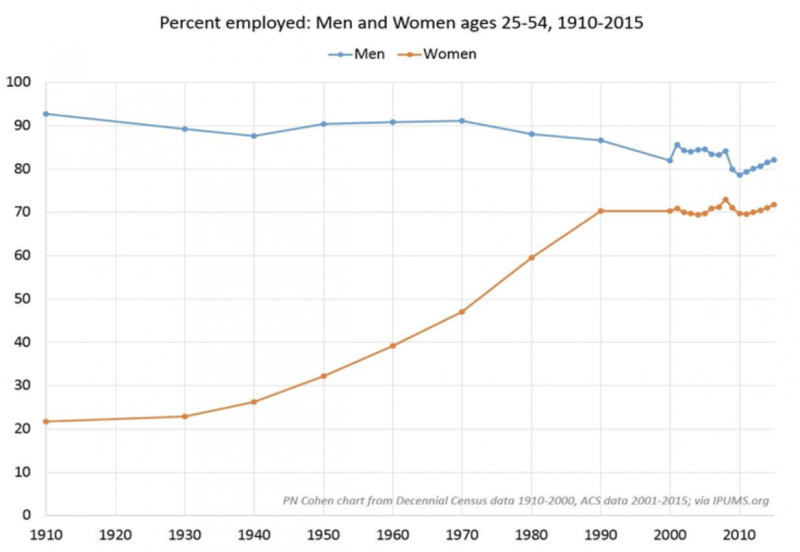

According to the Census Bureau, women comprised 47.4 percent of the civilian labor force in 2015—with 76.1 million females ages 16 and over participating—up from the 2014 Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported figure of 46.8 percent.

This increase of women in the workforce is paralleled by the increase of women with college degrees. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that among women ages 25 to 64 who are in the labor force, the proportion with a college degree more than tripled from 1970 to 2014, increasing from 11.2 percent to 40.0 percent.

Women’s Income and Employment

In 2015, women ages 15 and older who worked full time, year-round had median annual earnings of $40,742, compared with men’s earnings of $51,212. Women’s earnings as a proportion of men’s earnings have grown over time.

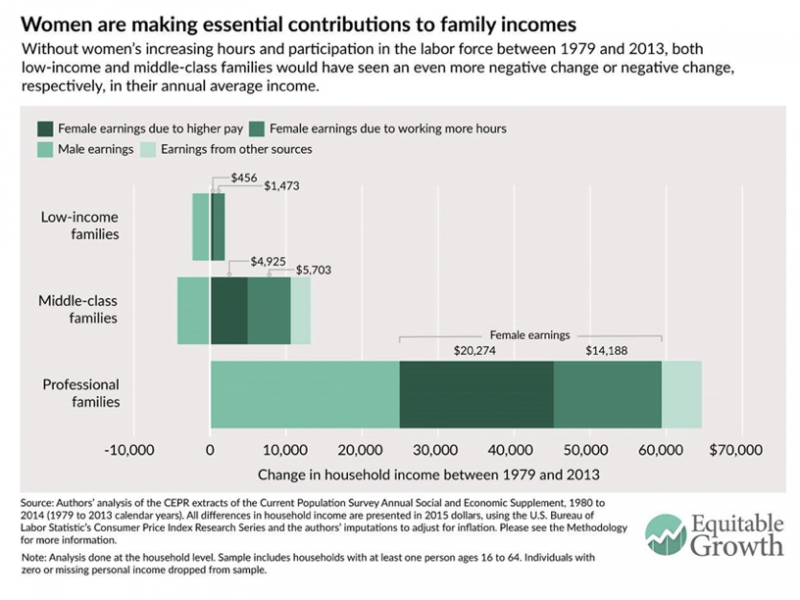

In 1979, women working full-time earned 62 percent of what men earned. In 2015, women’s earnings were 80 percent of men’s. Some women are even making more money than their spouses. In 9.7 percent of heterosexual married couples in 2016, the wife earned at least $30,000 more than the husband.

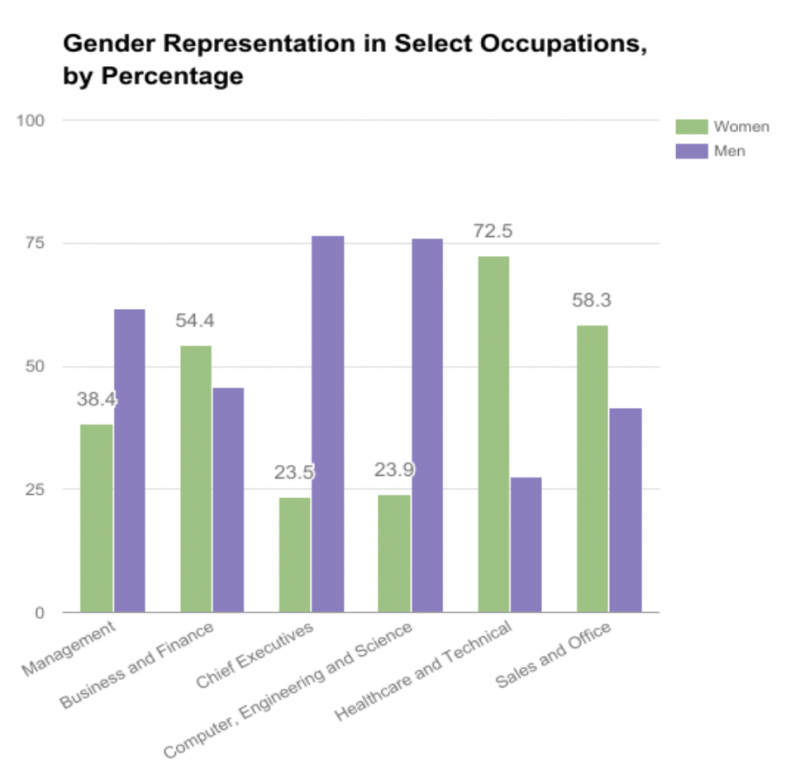

Although women have made historic progress in reaching pay parity, a significant percent gender wage gap persists. A recent Wells Fargo report, The Girl with the Draggin’ W-2, affirms that gender differences in occupation are responsible for more than half of the wage gap, as women continue to be underrepresented in higher-paying professions. Glassdoor reports that nine of the 10 highest-paying college majors like Physics and Computer Science and Engineering are male-dominated, while six of the 10 lowest-paying majors like Social Work and Anthropology are female-dominated.

Being paid less money for the same work hinders women in their attempts to build wealth, support families and become homeowners. Increasing female presence in STEM fields and higher-paying industries, especially in C-suite or senior executive positions, will help eliminate the wage gap. As more women earn college degrees and obtain higher-paying occupations predominately held by men, we should see an improvement in the next five to ten years of more than half of the wage gap. However, if the increased presence of women in higher paying jobs does not affect the gender wage gap, we will have to dig deeper into the unexplained wage gap referenced by The Girl with the Draggin’ W-2.

Women Professionals in STEM and Other Fields

While men have predominated STEM careers in previous years, more women are growing in computer, engineering and science occupations. For instance, women comprised 43.9 percent of life, physical and social science scientists in 2015, the highest percentage of women among all STEM occupations. The greatest representation of women among all STEM fields is in social science, where women comprise 63 percent of scientists.

The percentage increase of women in higher-paying occupations is astounding. Between 1970 and 2010, women civil engineers increased by 977 percent; pharmacists by 434 percent; physicians and surgeons by 334 percent; and lawyers and judges by 681 percent.

Percentage of Women in Select Occupations

|

1970 |

2006-2010 |

|

|

Registered nurses |

97.3 |

91.2 |

|

Dental assistants |

97.9 |

96.3 |

|

Cashiers |

84.2 |

74.7 |

|

Pharmacists |

12.1 |

52.6 |

|

Accountants |

24.6 |

60.0 |

|

Computer programmers |

24.2 |

24.4 |

|

Physicians and surgeons |

9.7 |

32.4 |

|

Lawyers and judges |

4.9 |

33.4 |

|

Police officers |

3.7 |

14.8 |

|

Civil engineers |

1.3 |

12.7 |

Source: 1980 and 1970 Census of Population Supplementary Reports – Detailed Occupation of the Experienced Civilian Labor Force by Sex for the United States and Regions, and EEO Tabulation EEO-ALL1R based on 2006-2010 American Community Survey

More women are also working in business, rivaling the rate of male participation. The percentage of women age 16 and older in 2015 who worked in management, business and financial occupations was 14.2 percent, compared with 15.8 percent of employed men.

Women’s Attainment of Higher Education

Women make up the majority of college students today: 12.5 million women were enrolled in undergraduate college and graduate school in 2015, comprising 55.4 percent of all college students.

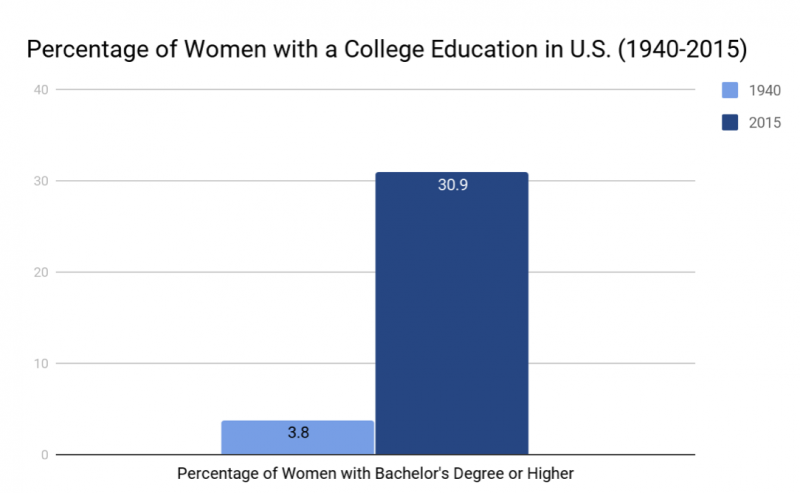

In 1940, a mere 3.8 percent of women held college educations; over 70 years later, this number has grown exponentially and 2015 U.S. Census Bureau data reveals that 30.9 percent of women had a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Increase of Women Entrepreneurs

We are seeing an encouraging growth of women-owned businesses in the United States, which are becoming a significant contributor to the American economy. There were an estimated 9.9 million women-owned firms in the U.S. in 2012, rising 26.8 percent from 7.8 million in 2007.

Women are Becoming More Independent

Once married, women usually leave their family homes to live with their husbands, but today’s young women are delaying marriage. Only 30 percent of women ages 18 to 34 were likely to be married in 2013 compared to 62 percent in 1940. Census Bureau data proves that now, on average, women enter marriage at age 27, compared to 21.5 years in 1940.

By earning higher degrees and higher wages, women have been able to increase their home buying activity and buying power. The significance of homeownership in a person’s life and its ability to cement career progress cannot be understated; it can mean the difference between independence and a stagnant future. The following section provides recent data on the status of women’s entrepreneurship in the housing ecosystem, as well as presents barriers women face.

Part Two: Women in the Housing Ecosystem

More women are becoming leaders in the housing ecosystem, especially in the real estate industry, from holding C-suite positions to owning and managing brokerages and firms in the U.S. However, there is still a substantial gender gap in the industry and a need for increased diversity and inclusion in managerial positions.

Women- and Minority Women-Owned Real Estate Firms

Women own a considerable amount of businesses in real estate, but the percentage of minority women business owners pales in comparison to the number of White women business owners. The 2012 SBO reveals that there were around 2.7 million real estate and rental and leasing firms with or without paid employees. Of these, over 700,000, or 26.5 percent, were women-owned.

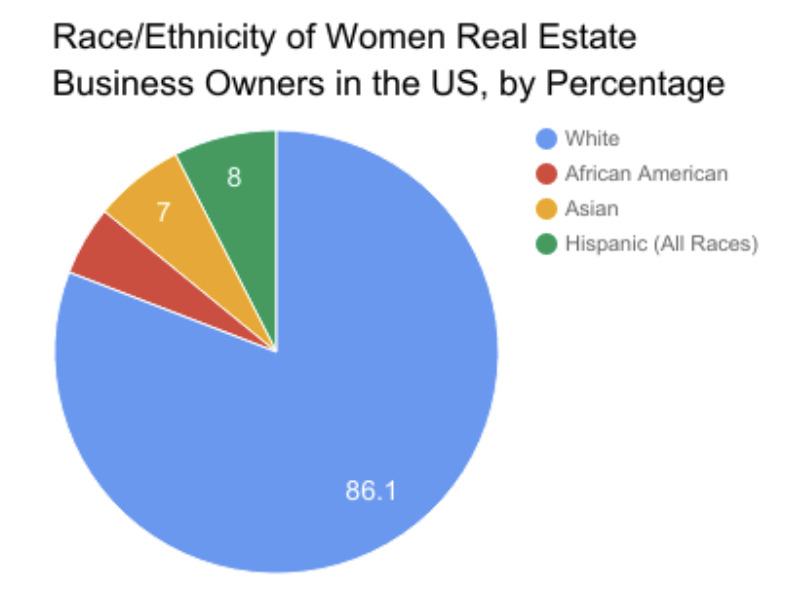

Of the women-owned firms, 86.1 percent of owners were white, 5.4 percent were African American, 7 percent were Asian and 8 percent were Hispanic. Minority women-owned real estate firms, almost 150,000 in total, comprised 5.6 percent of all U.S. real estate firms.

Source: 2012 Survey of Business Owners

Source: 2012 Survey of Business Owners

Women Brokers and Brokerage Owners in California

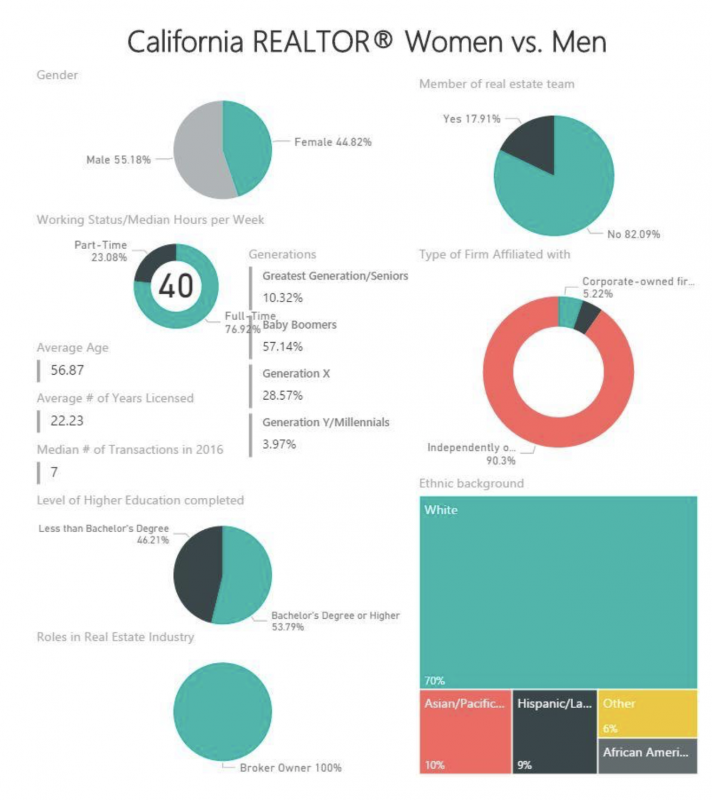

The California Association of Realtors (CAR) provides data, based on a survey conducted in 2017 with 81,000 participants, on women brokers and women brokerages in the state of California.

Women comprise about 42.3 percent of California realtors, compared to 57.3 percent that are men. Of these women realtors, 71 percent are white; 11 percent are Hispanic; 9 percent are Asian; 3 percent are African American; and 6 percent identify as two or more races, or another race or ethnicity.

The majority of women realtors in the state are Baby Boomers, at 53.3 percent. Generation X women make up 29.7 percent, 10.6 percent are Generation Y or Millennials, and 6.4 percent are seniors who belong to the Greatest Generation.

Women’s Roles in the Real Estate Industry Include:

o Sales agents and associate brokers, at 79 percent

o Broker owners, at 16 percent

o Managers, at 3 percent

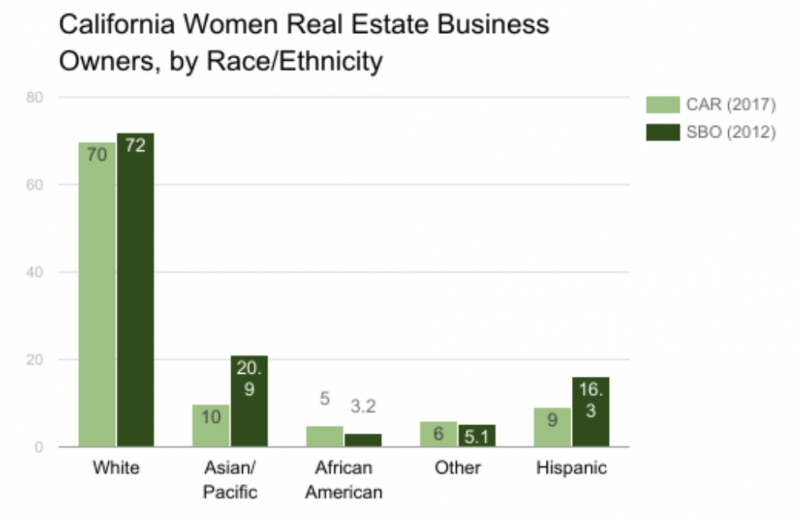

What about brokerage owners? Around 45 percent of brokerage owners in California are women, while men compose around 55 percent. Baby Boomers comprise the majority of women broker owners, at around 57 percent. Regarding ethnic background, 70 percent are white; 10 percent are Asian; 9 percent are Hispanic; 5 percent are African American; and 6 percent identify as other.

The infographic below from CAR provides more data on women brokerage owners in California.

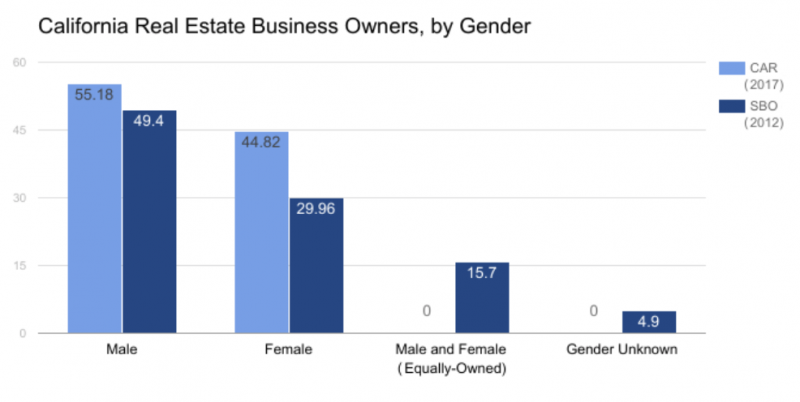

Let’s compare these numbers with data from the 2012 SBO, which provides information on “Real Estate and Rental and Leasing” firm owners in California. With a total of 340,961 firms, this category is much broader than just brokerages, including real estate lessors, equipment lessors and lessors of nonfinancial intangible assets; thus, this data is expected to differ from CAR’s, which encompasses brokerages only.

Below are graphs, created by NAWRB, which compare data between CAR and the 2012 SBO. Graph I shows a percentage breakdown of the gender of real estate firms and brokerage owners in California. Graph II features data on women brokerage owners and real estate firm owners in California, by race and ethnicity.

Source: California Association of Realtors & 2012 Survey of Business Owners

Source: California Association of Realtors & 2012 Survey of Business Owners

Gender and Minority Bias in Real Estate

A number of qualified women in the real estate have trouble reaching the C-suite, and a seat at the table, because of limited resources and bias in the industry. In commercial real estate, women and minorities face barriers in advancement due to a gender income gap, disparities in ethnic background of those in management positions and a lack of a company mentor or sponsor.

Commercial Real Estate’s Gender Gap

The CREW Network’s 2015 Benchmark Study Report reveals a significant pay gap between men and women in the industry, as well as inequalities regarding positions and job satisfaction. The median annual compensation, which includes bonuses and profit sharing, was $115,000 for women, compared to $150,000 for men. This represents an approximate 23 percent income gap, meaning that men in commercial real estate earn 30 percent more than women.

Although women in commercial real estate hold more senior level positions than ever before, men still outnumber women in C-suite positions. Of the study’s participants, 17 percent of men held C-suite roles compared to 9 percent of women.

Regarding satisfaction in the workplace, women have reported increased satisfaction with their careers and work-life balance since the CREW Network’s last report in 2010. However, women tend to report “higher levels of satisfaction at earlier phases of their careers.” Why does women’s satisfaction falter in the later phases?

Women are equivalent to men in satisfaction with career success, but they are less satisfied than men in job factors they consider most important, including job enjoyment, time spent with family and maximizing earnings potential. Men and women reported time spent with family as equally important, but men reported more satisfaction with the amount of time their job allows them. Both genders ranked lack of mentorship and concerns regarding work-life balance as key barriers to career success.

Mentorship is an important factor in women’s vertical growth, but many women are suffering from the lack of a mentor to help bolster their professional success. Women in commercial real estate report “relationships with internal senior executives as the number one factor supporting future advancement;” at the same time, women report lacking a relationship with a mentor or sponsor within the company as the number one barrier to career success and advancement. As Sponsor Effect 2.0: Road Maps for Sponsors and Protégés from the Center for Talent Innovation reveals, men in the workplace are 46 percent more likely than women to have a sponsor—a senior professional advocating for him and directly helping him obtain raises and promotions.

Diversity and Inclusion in Commercial Real Estate

While the commercial real estate industry generates more than $300 billion and has millions of employees, in a broad range of professions, it is still characterized as one of the least diverse industries. The 2013 Commercial Real Estate Diversity Report explores this problem by examining the industry’s employment patterns in five management job categories.

In its analysis of 166,554 jobs, the report breaks down the employment patterns, in terms of diversity, of senior executives and mid-level managers, among others, in commercial real estate.

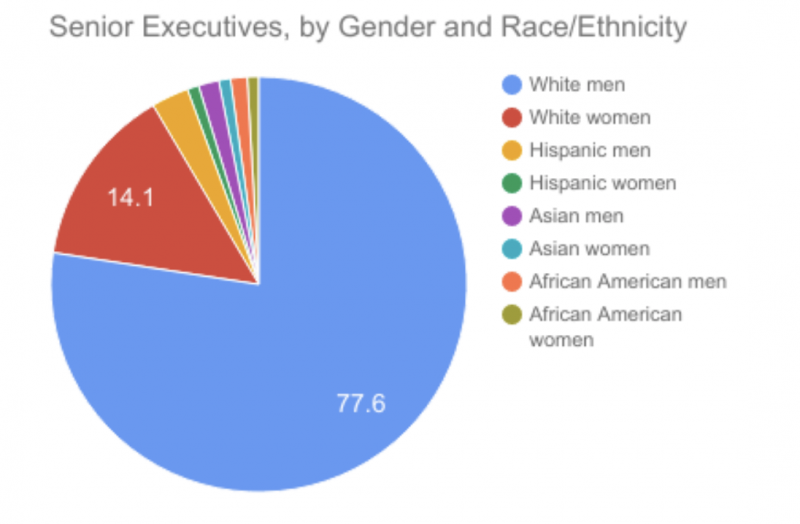

Senior Executives

Of the 13,773 senior executive jobs analyzed, 77.6 percent are held by white males. White women hold 14. 1 percent, and this 63 percent difference is the “widest achievement gap between White men and White women” of all job categories the report studied. Regarding minority representation in senior executive jobs,

• Hispanic men represent 2.9 percent;

• Asian men, 1.6 percent;

• African American men, 1.3 percent; and

• Hispanic women, Asian women, African American women, and women who

identify as “Other,” each hold less than 1 percent.

Source: 2013 Commercial Real Estate Diversity Report

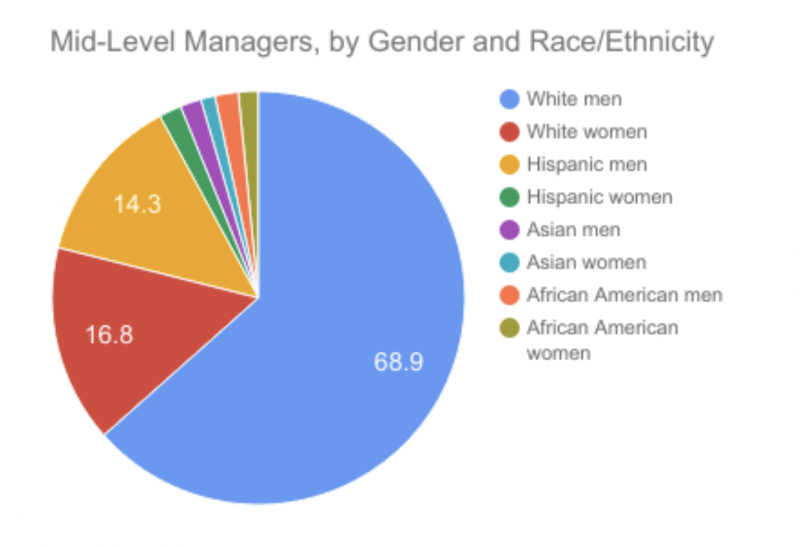

Mid-Level Managers

Regarding mid-level management positions, out of 47,844 jobs total, white men hold 68.9 percent, white women hold 16.8 percent and minorities collectively hold 14.3 percent.

Hispanic males are the largest representation of the minority group, holding 14.3 percent, a third of all mid-level manager positions held by minorities. Of the other two-thirds of minorities who are mid-level managers,

• African American men hold 2 percent;

• Hispanic women, 1.9 percent;

• Asian men, 1.8 percent;

• African American women, 1.7 percent; and

• Asian women hold a little over 1 percent.

Source: 2013 Commercial Real Estate Diversity Report

Ratio of Senior Executives to Mid-Level Managers

The report calculates the following ratios of senior executives to mid-level managers to demonstrate the chance workers of each ethnic background have of advancing into senior management:

• 1:3 for White men

• 1:4 for White women

• 1:5.3 for African American men

• 1:12.6 for African American women

• 1:5.7 for Hispanic men

• 1:8.9 for Hispanic women

Overall, men have a better chance of advancement than women of their same ethnic background; white women have a better chance of advancing to senior executive than most minority men, except Asian men; and minority women are less likely to advance into senior management than either white women or minority men.

A white male mid-level manager, for example, has a 1 in 3 chance of advancing to senior executive, while an African American female mid-level manager has about a 1 in 12 chance of advancing to senior executive. This study reveals that gender and ethnicity are significant barriers to advancement; minority women, in particular, are subject to a “double disadvantage” in gaining senior management positions.

Women in Finance

As the finance industry is a vital component of the housing ecosystem, it is important to make sure that women, especially minority women, are represented in it. There is a substantial gender gap of executive and managerial positions in finance, as well as in finance and insurance firm ownership, in the U.S.

In 2016, only 20 of chief executives included in the S&P 500 were women, a decrease from 24 in 2015. In addition, CNN reports that women held only “14.2 percent of the top five leadership positions” in this list of companies.

A Morningstar report released in June 2015 showed that only 9 percent of U.S. fund managers are women, out of a sample of 7,700 individuals who identified as portfolio managers. The number of women fund managers is striking, significantly less than the percentage of women that are doctors, 37 percent; lawyers, 33 percent; and accountants or auditors, 63 percent. Two percent of the industry’s assets and open-end funds were run exclusively by women, compared to 78 percent run exclusively by men.

Men outnumber women overall as employees in finance. Research by the Harvard Business School, from 2012, on 283 U.S. and European private investment firms states that women make up 17 to 23 percent of employees in the industry, “overwhelmingly found in marketing, HR, and other support functions.”

Some data, however, indicates a decrease of women in management positions. The Diversity Management: Trends and Practices in the Financial Services Industries after the Recent Financial Crisis report from the United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) shows that the representation of women at the management level in the financial industry declined from 49.1 percent to 47.3 percent between the years 2007 and 2011.

These numbers become smaller when we look at the senior management level. Women made up about 29 percent of senior management positions in this five year period, with a slight decrease from 30 percent in 2007 to 28.4 percent in 2011. Work needs to be done before we can see this slow growth become the upward trend for which we strive.

Progress in women’s representation in executive positions has been slow. The Oliver Wyman Women in Financial Services 2016 report shows that women represent 20 percent in financial services boards and 16 percent in executive committees, after an analysis of 381 financial service institutions in 32 countries. The report predicts that “financial services globally will not reach even 30 percent female Executive Committee representation until 2048.” This is an issue companies must take seriously because a lack of diversity could lower their performance and ability to stand out amongst competitors.

Women control 50 percent of private wealth in the United States and head one-third of all households, as the 2013 PwC: Mending the Gender Gap report reiterates, giving them a unique understanding and insight into a pivotal sector of the customer demographic. Studies show that a company with a gender-diverse board outperforms the competition with

• 42 percent higher returns in sales;

• 66 percent greater return on invested capital; and

• 53 percent higher return on equity

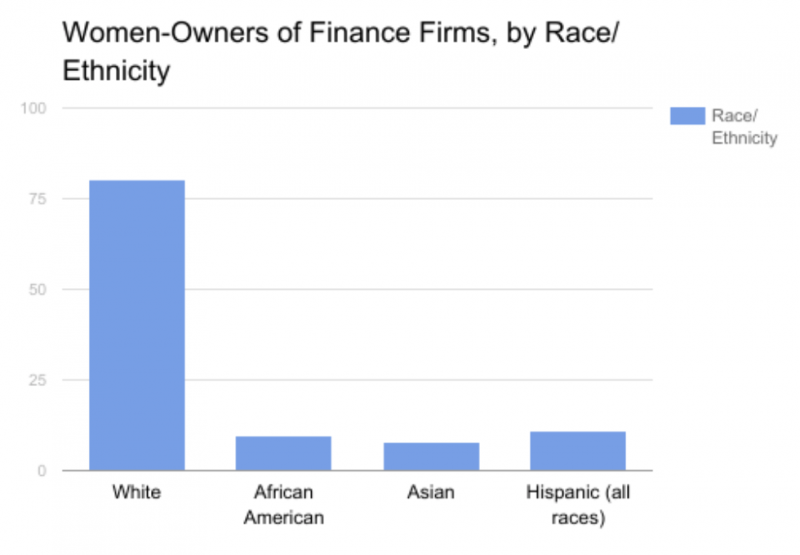

As we did for women in real estate, we’ll see how these statistics compare to data from the 2012 SBO. In 2012, women owned about 22.7 percent of all finance and insurance firms in the US. The chart below shows the representation of race and ethnicity among this group.

Source: 2012 Survey of Business Owners

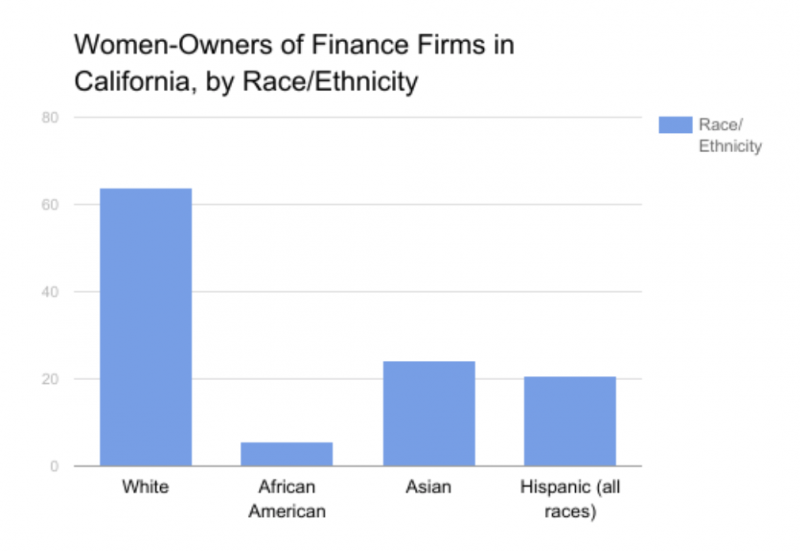

In California, women own about 27.3 percent of all finance firms, compared to 60.2 percent owned by men. The breakdown of the race and ethnicity of women-owners varies slightly of those found in the country as a whole. Symbolic of the diverse population present in the state, the representation of Asian and Hispanic women almost doubles; however, the representation of African American women decreases, from about 10 percent to 6 percent.

Source: 2012 Survey of Business Owners

Despite underrepresentation of women and minorities in finance, there is hope for improvement in upcoming years. Female CFOs’ salaries are growing at a faster rate than those of male CFOs at S&P 500 companies: an 11 percent increase compared to a 7 percent increase, according to analysis by Equilar and Associated Press. Moreover, in 2015, the median pay for female CFOs was $3.32 million, while male CFOs earned about $3.3 million; 60 female CFO’s and 437 male CFO qualified for the Equilar and Associated Press study.

Particular attention needs to be paid to mid-career women in financial services, where there is a greater gender gap compared to lower-level employees. Women are more likely to exit their careers at this critical stage, more so than in any other industry: “Female managers, senior managers and executives in financial services,” 2016 Oliver Wyman report claims, “are 20 percent to 30 percent more likely to leave their employer than their peers in other industries.” These women are faced with having to make sacrifices in their personal lives in order to advance with uncertain opportunity costs.

These unattractive trade-offs are due to a lack of flexible working options: limited support in household responsibilities; obscure and unequitable promotion processes and pay parity; and subpar integration of diversity and inclusion in work culture. In approaching these factors deterring mid-level career women from advancement to executive positions, companies need to innovate and implement structural solutions that target both culture and internal processes.

Women in Technology

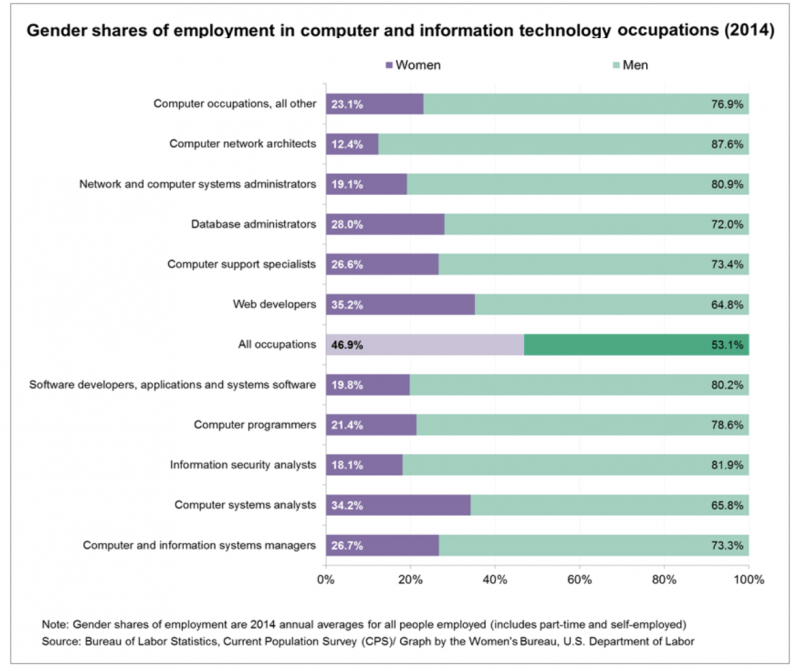

Technology is another field in which women are greatly underrepresented, and it’s a societal issue affecting the workforce. The chart below from the Bureau of Labor Statistics reveals the gender shares of employment in computer and information technology in 2014. While women made up over half of all occupations in technology, they were consistently underrepresented in specific occupations. Women were 21.4 percent of computer programmers, 35.2 percent of web developers and 26.7 percent of computer and information systems managers.

Today, women’s representation in technology occupations has not seen great improvement; in 2017, women hold only 25 percent of computing jobs. The rate of women in these positions has steadily declined since 1991, when there was a peak of 36 percent.

There is a dearth of women as business owners of startups. Women own only 5 percent of startups and hold 11 percent of executive positions of Silicon Valley companies, according to the Observer.

Not only are women underrepresented in executive positions, but women-led companies receive less investments than men-led companies. Venture capitalists invested $1.46 billion in women-led companies in 2016; male-led companies gained $58.2 billion in investments the same year.

Like women in commercial real estate, women in technology also face gender pay gaps in the same occupation. Women will receive lower salary offers from their male counterparts for the same job at the same company 63 percent of the time. For younger women under the age of 25, their earnings are, on average, 29 percent less than men of the same age.

Gender pay gaps, along with gender bias in the workplace and a lack of female mentors, are some of the barriers women professionals face, reported by the ISACA’s 2017 Women in Technology Study.

Addressing these barriers can contribute to the underrepresentation of women in the industry. ISACA’s infographic on the following page, illustrating survey results of over 500 participants, shows that minimal numbers of female leaders and role models; a lack of work/life balance; and limited amount of educational institutions that encourage girls to pursue careers in technology are some of the highest-ranked reasons for technology’s status as a male-dominated field.

The good news is that young girls show interest in technology careers: about 74 percent express interest in STEM fields and computer science. However, they may be deterred when they do not see many women represented in technology that can be inspirational role models. As these young girls become older, they may be discouraged by statistics indicating a gender pay gap and gender bias. An increase of women mentors in technology could significantly help women’s advancement, thereby increasing the number of women in male-dominated positions such as senior executives, and encourage future generations to be tenacious in pursuing their dreams.

Part Three: Women’s Homeownership

Current Women’s Homeownership Statistics

The desire for homeownership is present and firm among women. With the prevalence placed on pay parity, which would significantly increase their access to homeownership, female buyers are poised to enact a great impact on the housing industry.

According to 2014 Census Bureau data, there are 18,057,000 female homeowners in the U.S. Ten million live alone, 6.7 million live with relatives without a husband present and 1.3 million live in two-or-more-person households.

Source: 2015 American Community Survey

U.S. Census Bureau data reveals that there are a total of 116,926,305 occupied housing units. Married-couple families make up the majority of occupied housing units at 48.3 percent, but single women comprise a formidable amount. Female householders with no husband present comprised 13 percent of total family households, in comparison with 4.8 percent of male householders with no wife present. Of female householders, single women aged 35 to 64 years old comprised 7.7 percent of householders, while 3.3 percent were single women between the ages of 15 and 34.

According to the National Association of Realtors (NAR), in 2016, women accounted for 17 percent of homebuyers, and the average woman homebuyer touted a median income of $55,300. This was an increase from the previous year in which women were 15 percent of homebuyers with a median income of $57,300. These findings depict women’s strong desire to become homeowners, as women homebuyers’ lower wages did not negatively affect their buying activity. How are women doing this? Through hard work, good planning, determination and sacrifice. Whether it’s time with family, preferred neighborhoods or dream homes, women are doing what it takes to achieve homeownership.

Despite women homeowners’ growth, they are still disadvantaged when compared to men. While single women homeowners statistically outnumber single men homeowners, there is a home value disparity between the genders. In the U.S.—principally due to women’s lower buying power—homes owned by single men are worth 10 percent more; and, as a result of their higher worth, single men’s homes appreciate 16 percent faster than homes owned by single women.

Not only are single women disadvantaged in regards to the value of their homes, but they remain behind indefinitely. This has significant consequences—in career, retirement, family planning, to name a few—all stemming from the fact that the property and wealth of women homeowners does not accrue as high, or as fast, as that of men homeowners. Women are continually receiving less for their work, and now for their money as well. How can they be expected to succeed with these imbalances?

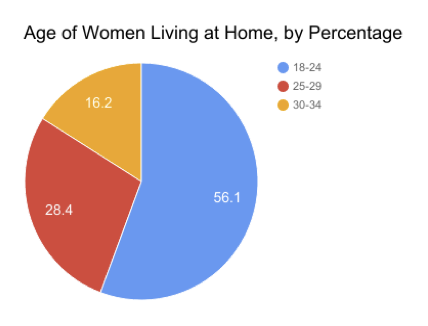

One of the key barriers in women’s homeownership is affordability, which has led more women to delay independent living. The Pew Research Center reports that 36.2 percent of women aged between 18 and 34 lived with their family, parents or other relatives, excluding their spouse in 1940. In 2014, 36.4 percent of women in this age group were still living with their families, an increase from 75 years ago.

Graph 2 illustrates the age break-up for women living with family as of 2014.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

One explanation for why women between the ages of 18 and 24 make up the majority of women still living at home could be that college students are more likely to live with their families than young adults not enrolled in college (45 percent versus 33 percent). Also, once women marry, they typically move out of their family’s home to live with their husbands, but an increasing amount of women are delaying marriage.

The following factors influence women’s homeownership and economic self-sufficiency:

low income, job instability, low levels of education, insufficient savings, poor credit histories, discrimination in mortgage lending, and lack of family or community support, such as access to child care. Moreover, gender inequality, along with disparities in class, race and ethnicity, compounds the effects of barriers preventing women’s economic growth.

The next section will explore these factors in depth.

Factors that Influence Women’s Homeownership

Employment and Income

A higher percentage of women are participating in the labor force, taking careers in fields that were once male-dominated, and are earning greater incomes as they pursue higher education.

Women’s earnings have increased relative to men’s earnings; in 2015, women working full time, year-round, earned 80 percent of men’s earnings. For comparison, women working full time earned 62 percent of what men earned in 1979.

However, there is a significant gender gap in median earnings for workers 25 years and older who pursue higher education. The U.S. Census Bureau data reveals that females with a Bachelor’s degree had median earnings of $41,763 in 2015, which is about $20,000 less than what males with a Bachelor’s degree earned. The gender pay gap increases to an estimated $30,000 for workers ages 25 and older who have graduate or professional degrees.

A 2009 study, Occupational Feminization and Pay: Assessing Causal Dynamics Using 1950-2000 U.S. Census Data, further complicates the wage gap issue by showing that wages in fields like biology and design were higher when the industries were male-dominated, and decreased as female participation increased. Similarly, programming wages increased as the field shifted from female to male predominance. These findings suggest that when lower wages don’t precede women, they can find a way follow them.

As more women continue to participate in the labor force, they make up a greater percentage of occupations that were once male-dominated. In 2015, women comprised the following percentages of full time, year-round workers in select occupations:

Source: 2012 Survey of Business Owners

The 2015 American Community Survey reveals occupations in which women’s earnings were 100 percent or more of men’s earnings, including: architectural and engineering managers; wholesale and retail buyers; chemical engineers; news analyst, reporters and correspondents; dieticians and nutritionists; residential advisors; electricians; and industrial truck and tractor operators. The occupations in which women’s earnings as a percentage of men’s earnings were the lowest (out of those industries and occupations reported) included:

o Pressers, textile garments, and related materials at 62.1 percent;

o Personal financial advisors at 61.9 percent;

o Judges, magistrates and other judicial workers at 59.1 percent;

o Financial specialists at 54.6 percent; and

o All legal occupations at 53.3 percent.

Entrepreneurship

Many women are crafting careers as entrepreneurs and originating their own lucrative businesses, especially in the housing ecosystem. The 2012 Survey of Business Owners (SBO) reports that there are 9.9 million women-owned firms in the United States, rising 26.8 percent from 7.8 million in 2007. The survey shows that women own 35.8 percent of U.S. firms, and they constitute the majority of firms in the following sectors: 62.5 percent of healthcare and social assistance, 54.2 percent of educational services and 51.8 percent of “other” sectors.

Source: 2012 Survey of Business Owners

The estimated receipts from women-owned firms were $1.4 trillion, an increase of 18.7 percent from 2007. Minority women-owned firms contributed a momentous $265 million to the receipts of all women-owned firms.

Entrepreneurship is a powerful tool for the creation of wealth and upward mobility. The Global Wealth 2016 report from the Boston Consulting Group reveals that 30 percent of private wealth in the world belongs to self-made women. According to the study, of women with a private net worth of at least $100,000, 44 percent were entrepreneurs or employees who had earned their wealth outside of work.

With the prevalent gender gap and imbalances in the professional arena, is it a surprise that wealthy women often amass their earnings through entrepreneurship, by making their own rules instead of following those of the disparate workplace?

Education

A greater percentage of women are pursuing higher education, which has had the positive effect of increasing their median earnings and buying power. According to 2014 U.S. Census Bureau data, 30.2 percent of women had a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 3.8 percent in 1940.

In 2015, 12.5 million women were enrolled in either undergraduate or graduate school, comprising 55.4 percent of all college students. The percentage of women ages 25 and older who earned a bachelor’s degree increased to 30.9 percent, compared to 30.3 percent of men 25 years and older.

Education is pivotal because women’s weekly earnings increase in proportion to their level of education. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports that female full-time wage and salary workers ages 25 and older with only a high school diploma had median weekly earnings of $578 in 2014; women with a bachelor’s degree or higher, on the other hand, had a weekly median income of $1,049.

Women’s Poverty

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, more than 1 in 4 families with children under the age of 18 are headed by a single parent and more than 3 out of 4 single parent families are headed by a female.

Insufficient income and employment opportunities have placed a significant number of households headed by a female below the poverty level. According to 2015 Census Bureau data, 15.5 percent of individuals and 5.6 percent of married couples live in poverty. In contrast, 30.6 percent of families with a female householder, and no husband present, are below the poverty level. Of these, 40.5 percent have children under 18 years old and 46.3 percent have children only under 5 years of age.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Living in a financially underprivileged state can negatively affect the quality of these families’ lives and prevent mothers from rising above the poverty line to afford the comfort and stability of homeownership.

As we will now address, even in the process of home buying, women face persistent obstacles.

Discrimination in Mortgage Lending

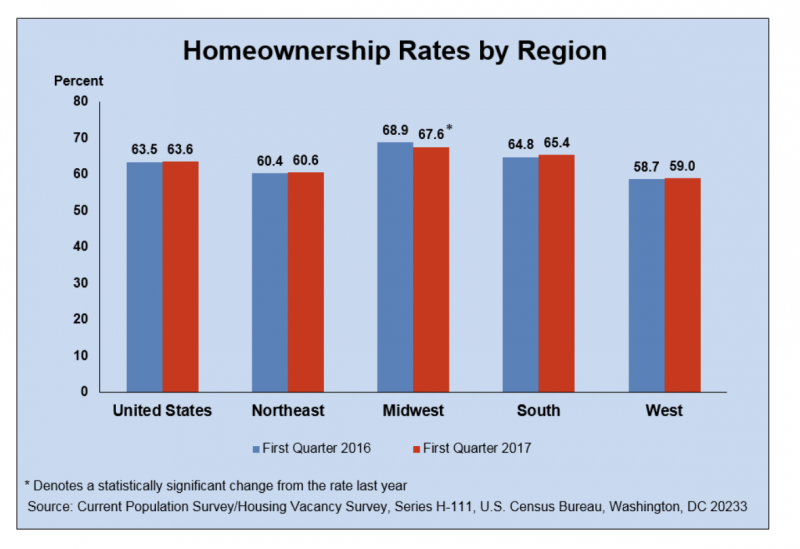

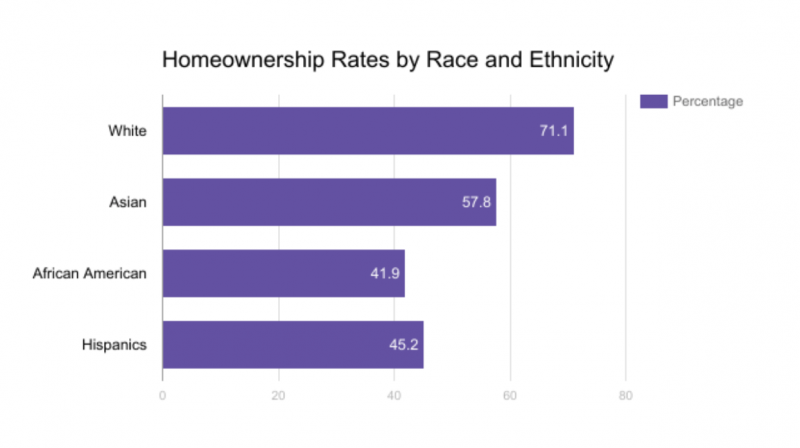

The current homeownership rate in the U.S. is 63.6 percent, but the rates among different racial and ethnic groups vary considerably. The rate of homeownership for whites is 71.1 percent; for Asians, 57.8 percent; for African Americans, 41.9 percent; and for Hispanics, 45.2 percent. Difficulty in receiving credit, institutional discrimination in mortgage lending and disparities in home values are obstacles facing minorities, especially low-income women of color and their families, according to Dr. Sharon Lindhorst Everhardt, of Troy University.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Despite equal repayment performance, single borrowers, particularly women, have higher mortgage rates; from 2004 to 2014, the average rate for female-only borrowers was 5.48 percent compared to 5.41 percent for male-only borrowers, according to the Urban Institute. A 2011 Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics study also shows that on average, women pay more for mortgages than men; women’s mean interest rates are .4 percent higher than men’s.

Sub-prime mortgages, which come with high interest rates and high mortgage payments, effectively remove any equity built into the home. As single women only have one paycheck to subsist on, they are at risk of unforeseen expenses such as home repairs and unanticipated bills. In these cases, homeownership may become more of a liability than a resource for independence and wealth-accumulation.

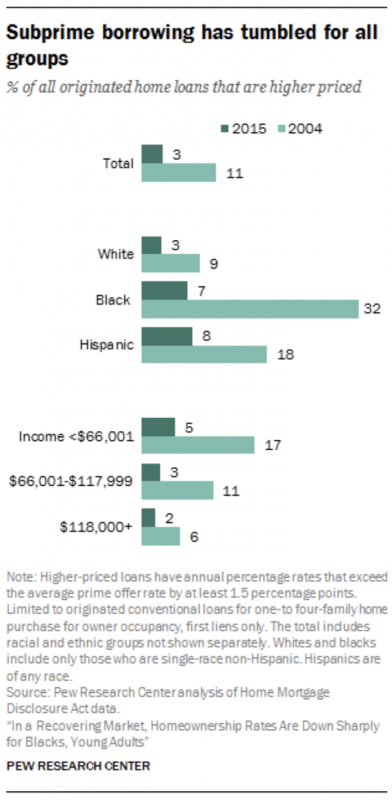

Minorities have difficulty receiving credit, and home values in their neighborhoods were disproportionately affected in the housing boom and bust. Moreover, minorities’ mortgage applications are rejected at a higher rate than those of white applicants. According to Pew Research Center analysis of Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data, in 2015, 19.2 percent of Hispanic applicants and 27.4 percent of black applicants were denied mortgages, compared to 11 percent of white and Asian applicants. For Black applicants, credit history is the number one cited reason for mortgage rejections; for the three other groups, debt-to-income ratio was the foremost explanation.

Contributing to lower affordability, mortgage rates also enact an uneven impact on homebuyers. In 2015:

• 60 percent of Black householders and 65 percent of Hispanic householders had mortgage rates below 5 percent, compared to 73 percent of white householders and 83 percent of Asian householders

• 18 percent of Hispanic householders and 23 percent of Black householders had mortgage rates of 6 percent or more, compared to 13 percent of white householders and 6 percent of Asian householders

Potential homebuyers are subject to stringent lending practices, which the Pew Research Center reports are more stringent today than in the early 2000s, when home values were climbing. Tighter credit standards may be deterring some people from entering the market. Since 2004, loan applications have decreased significantly, especially for African American and Hispanic applicants. Moreover, the higher priced loans minority borrowers relied on have become sparse after the stock market crash. For instance, 32 percent of loans to African American borrows were subprime in 2004; in 2015, subprime loans made up 7 percent.

Ostensibly all racial and ethnic groups face tough credit standards, but some minority groups are significantly unable to meet them, which also deters them from applying for them in the first place. In the long run, this may contribute to a lower homeownership rate.

Compared to pre-recession peak levels, the home values in predominantly Hispanic neighborhoods fell an average of 46.3 percent, and by 32.1 percent in predominantly African American communities. During the same time, home values in largely white areas dropped by 23.6 percent, and by 19.2 percent in mostly Asian areas. While home values in mostly white and Asian neighborhoods have reached, or are close to reaching, peak levels, Zillow states that African American and Hispanic communities “have farther to climb.”

Family and Community Support

From her interviews with several low-income single mothers, including women of color, Everhardt concluded that supportive networks are pivotal in helping them gain education, income and savings towards their ultimate goal of self-sufficiency and homeownership. A community-based support center is helpful for providing adequate childcare and additional resources like income, so low-income women can work towards educational degrees, take financial classes, go to job interviews and take on additional paid work. These are important steps that could bring these women closer to being able to afford a home.

Part Four: Trends and Barriers to Address

Increasing Women’s Homeownership

Women are achieving higher degrees and outnumbering men in the college student population. They are also increasing their representation in career fields that have been predominated by men, especially in STEM. In attaining higher levels of education, women are earning higher wages and increasing their purchasing power. However, gender imbalances still need to be overcome so that women are not unfairly disadvantaged compared to men.

Five-Year Trend in Women’s Homeownership

Taking a look at U.S. Census Bureau data, the percentage of single women homeowners has increased slightly, about 0.4 percent, from 2010 to 2015; households have only increased by about two million during this period. The chart below shows the percentage of single women householders, compared to the percentage of single men householders.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

The percentage of female householders has remained at 13 percent from 2013-2015. This plateau may continue into 2017, but we should hopefully see an increase, even if under one percent, in 2020, especially as more Millennials will become first-time homebuyers. 2016 Zillow data reveals that the median age of home buyers is 36, and first time home buyers account for 47 percent of all household purchases.

Barriers to Women’s Homeownership

The factors influencing women’s homeownership are various and can become formidable barriers to women seeking self-sufficiency and wealth accumulation through owning a home. Many studies, such as Dr. Lindhorst Everhardt’s study on barriers that low-income women and their families face, show that education, employment, savings, discriminatory practices in mortgage lending, and a lack of community support each play roles, often intersecting, which limit low-income women’s ability to independently afford a home. When formulating solutions for increasing women’s homeownership, these barriers, individually and as a whole, must be taken into account. An optimum solution will provide women the tools to overcome them.

Education: A lack of education can be a barrier to homeownership, because a lack of proper credentials can prevent low-income women from obtaining higher-paying jobs, participating in mentorships, and accessing networks that will provide them with better opportunities in the future.

Employment: Unemployment, job instability, and underemployment are major barriers to women’s homeownership, especially since prospective homebuyers need to show evidence of a steady income when applying for a loan from mortgage lenders. In addition, gender bias and a lack of mentorship may prevent women from advancement to higher management and executive positions, thus a greater income.

Income and Savings: The gender pay gap prevails in many fields; women currently earn, on average, 80 cents for every dollar men earn. A low-paying job that may cover basic expenses, such as food, transport, and bills, prevents women from building a savings towards their goal of homeownership.

Education and employment play a role in low-income women’s ability to save. Without a degree, these women will not meet the requirements to obtain higher-paying jobs that will allow them to save money towards a down payment while still covering basic expenses.

Discriminatory Practices in Mortgage Lending: Minorities face drawbacks when trying to achieve loans from mortgage lenders. Statistics show that minorities’ mortgage applications are declined at a higher rate than those of non-minorities. This type of institutional discrimination negatively impacts the ability of low-income minority women to take the required step towards homeownership.

Supportive community: Low-income women, especially those who are heads of households, benefit from having a support system in their community or family to help clear barriers to achieving a higher education, a greater income, and starting a savings. These social networks can help women by providing supplemental income or adequate childcare so that they can eventually reach a point of self-sufficiency.

Expanding Diversity and Inclusion in the Housing Ecosystem

Growth of Women-Owned Businesses in the United States

The rate of women-owned businesses grew significantly from 2007 to 2012: the percentage of women-owned businesses has increased about 7 percent for all firm types; 2 percent for real estate and leasing firms; and 3 percent for finance and investment firms. See the bar graph below for the growth of women-owned businesses during this five-year period.

Source: 2007 SBO & 2012 SBO

In upcoming data from the 2017 SBO, released next year, we will hopefully see a continuing upward trend of women-owned businesses. A more concerted effort will have to be directed at increasing the slow growth of women in C-suite positions, especially in industries such as finance where women’s representation is decreasing at the senior management level, according to the 2013 GAO report.To make sure of this, we must address the following barriers that prevent, as well as discourage, women from advancement into higher-level employment.

Obstacles to Female Advancement

Women professionals face the following barriers in the housing ecosystem: a persistent 23 percent income gap and bias in their advancement to C-suite positions. Both of these must be addressed in order to motivate and propel more women into executive positions.

Bias against women, and minority, advancement must be countered at all levels of employment, with a starting point at corporate management. Companies should challenge gender bias in creating a work culture that bolsters the advancement of their female employees. This can be helped by the implementation of mentorship programs within their organization. Having a mentor or sponsor within their company is an invaluable asset for women’s advancement from middle management to the C-suite; in contrast, not having access to one can harm women’s motivation for advancement.

“As a consequence to these barriers,” the Commercial Real Estate Diversity Report states, “women are less likely to aspire to C-suite positions.” To make sure women in the housing ecosystem keep aspiring for vertical growth, we must make way for that aspiration by clearing the barriers which obstruct it.

Bibliography*

2012 Economic Census, Survey of Business Owners (SBO), “Statistics for All U.S. Firms by Industry, Gender, Ethnicity, and Race for the U.S., States, Metro Areas, Counties, and Places: 2012,” U.S. Census Bureau, December 15, 2015.

2015 Benchmark Study Report: Women in Commercial Real Estate, Commercial Real Estate Women (CREW) Network, March 29, 2016.

“ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates,”2015 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau, September 15, 2016.

“Authors’ analysis of the CEPR extracts of the CPS Annual Social Supplement, 1980 to 2014,” Equitable Growth.

Beardsley, Brent et al., Global Wealth 2016: Navigating the New Client Landscape, Boston Consulting Group, June 15, 2016.

“California Realtor® Women vs Men,” California Association of Realtors (CAR), 2017.

Chamberlain, Andrew, Dr., and Jyotsna Jayaraman, The Pipeline Problem: How College Majors Contribute to the Gender Pay Gap, Glassdoor, April 19, 2017.

Cheng, P., Lin, Z., & Liu, Y., “Do Women Pay More for Mortgages?”,Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 43, 2011.

Commercial Real Estate Diversity Report, CRE Diversity, August 2013.

“Current Population Housing Survey, Series H-111,” U.S. Census Bureau, 2017.

Davis, Erin and Laura PavlenkoLutton, Morningstar Research Report: Fund Managers by Gender, Morningstar, June 2015.

Diversity Management: Trends and Practices in the Financial Services Industries after the Recent Financial Crisis, United States Government Accountability Office (GAO), April 2013.

“First-time Buyers, Single Women Gain Traction in NAR’s 2016 Buyer and Seller Survey,” National Association of Realtors (NAR), October 31, 2016.

Fry, Richard, and Anna Brown, In a Recovering Market, Homeownerships Are Down Sharply for Blacks, Young Adults, Pew Research Center, December 15, 2016.

The Future Tech Workforce: Breaking Gender Barriers, ISACA, 2017.

Goodman, Lauire, Zhu, Jun, & Bing Bai, Women Are Better Than Men at Paying Their Mortgages, Housing Finance Policy Center, Urban Institute, September 2016.

Hewlett, Sylvia Ann, et al., Sponsor Effect 2.0: Road Maps for Sponsors and Protégés, Center for Talent Innovation, 2012.

Levanon, Asaf, England, Paula, & Paul Allison, Occupational Feminization and Pay: Assessing Casual Dynamics Using 1950-2000 U.S. Census Data, Social Forces 88.2, University of North Carolina Press, December 2009.

Lietz, Nori Gerardo, “In the Hot Finance Jobs, Women Are Still Shut Out,” Harvard Business Review, July-August 2012.

LindhorstEverhardt, Sharon, “Meeting the Needs of Mothers and Families? Family Self-Sufficiency Programs and Goals of Homeownership,” Michigan Family Review 18.1, University of Michigan, 2014.

“Median Earnings in 2015 by Sex and Educational Attainment for the Population 25 years and over,” U.S. Census Bureau, September 15, 2016.

“Mending the Gender Gap: Advancing Tomorrow’s Women Leaders in Financial Services,” PwC Financial Services People & Change, Pricewaterhouse Coopers LLP, May 2013.

Million Women Mentors and STEM Connector, Women’s Quick Facts: Compelling Data on Why Women Matter, New York, Morgan James Publishing, 2017.

“Occupancy Characteristics: 2011-2015 ACS 5-Year Estimates,” 2015 American Housing Survey, Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and U.S. Census Bureau, November 17, 2016.

“PIN Cohen chart from Decennial Census Data 1910-2000, ACS Data 2001-2015,” IPUMS.

Ritholtz, Barry, “Where Are the Women in Finance?”,Bloomberg View, February 24, 2016.

Schumaker-Krieg, Diane et al., The Girl with the Draggin’ W-2, Wells Fargo Economics Group, Wells Fargo, February 27, 2017.

“Selected Housing Characteristics,” 2015 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau, September 15, 2016.

“Selected Economic Characteristics,” 2015 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau, September 15, 2016.

“Selected Social Characteristics,” 2015 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau, September 15, 2016.

“Women’s History Month Press Release,”U.S. Census Bureau, March 2017.

“Women in Financial Services 2016, ”Oliver Wyman, Marsh & McLennan Companies, June 2016.

“Wonkblog analysis of CPS data via IPUMS,” Wapo.st/Wonkblog.

Zillow, “Black Applicants More Than Twice as Likely as Whites to be Denied Home Loans,” Zillow, February 9, 2016.

*This report offers analysis from the latest available data regarding women’s homeownership and women professionals in the housing ecosystem. It is our hope that more data will be collected and reported so that we may better articulate the status of gender equality and opportunities for women’s economic and professional growth within the industry.

Login

Login