NAWRB would like to give special thanks to NAWRB Diversity & Inclusion Leadership Council (NDILC) Member Erica Courtney, President of 2020vet and Zulu Time, U.S. Army Aviation Major, NATO Gender Advisor, and California Commissioner on the Status of Women & Girls, appointed by California Governor Gavin Newsom, not only for her service but also for her contribution to NDILC and the NAWRB community.

Erica Courtney is a U.S. Army veteran having served in various positions to include; military police, scout helicopter pilot and paratrooper. As a trailblazer, she was part of the first group of women to go Cavalry and the first to graduate the Advanced Armor Cavalry Course. Erica continues to serve the nation as a Major in the U.S. Army Reserve under the Joint Chiefs of Staff working on Women, Peace and Security initiatives as the only NATO certified Gender Advisor working at political and strategic levels.

To celebrate Veterans Day, NAWRB is releasing Erica Courtney’s story on being a Woman Veteran. Don’t miss this impactful life story about the trials and tribulations of being a woman veteran and how Erica Courtney persevered for the United States of America!

Part 1 of 6

I am proudly part of the 1.4 percent of American women who served in the military. The day I signed the paperwork to join as a teenager the Gulf War kicked off and I watched tanks fire through the night on TV thinking, “What in the world did I do?” Having grown up in surf city USA (Huntington Beach, CA), I was never exposed to the military. To emphasize this point, the first time I walked into an Army recruiting office I had sand in my hair and sun-kissed skin; I was with a friend of mine and said, “Hi, I am thinking about joining the Marines,” not even understanding the difference in services. The recruiter took a few looks at us, confused, and had to be thinking, “Sucker!” Having always been athletic and adventurous, I thought why not. I would rather try something and hate it than wonder what it would have been like. College was a bore and I was ready for the unknown.

“Get off the bus, you maggots!” Welcome to Military Police Basic Training. What was wrong with these people? Why so much yelling? Okay, bag in hand off the bus I went into the barracks. This is actually where Hollywood gets it right. There’s lots of yelling, climbing, learning, bonding and trying to stay under the radar. Except, I learned early on that was pretty hard for me. I was a runner breaking six-minute miles, and one particular drill sergeant could not stand that there was a female in his fast group and did whatever he could to break me. He was an infantry man where they did not work with women. There were many days of unnecessary hazing to the point he was counseled by the officers. He tried to make me cry, but failed. Many more attempts would follow. I learned early, never let them see you sweat and there is no crying in uniform.

Congratulations. First assignment, Germany. Away from everything I knew. I showed up and was nicknamed Private Benjamin. I was tasked with 12 to 15-hour patrol days and nights responsible for enforcing the Post Commander’s rules and regulations. I was 19 carrying a side arm and had authority most 19-year-olds couldn’t fathom. For any accident that involved an American within 200 miles I would drive out in my VW van with no heater and a blanket draped over me. I’d get out, wipe snow off signs, and arrive to some horrific scenes thanks to the autobahn and no speed limits. The Polezi refused to show up so I had to handle the situations; my first taste of being a first responder and having to show calm and exude control of situations. Our wartime mission dealt with POWs, security and convoy assistance. As the lowest ranking, I got assigned an M60 machine gun then a SAW and had to sleep with this metal thing in my sleeping bag. I was so cold at times I could barely get my fingers to work to shoot, but it’s amazing how warm it gets once in use. After winning over my superiors they assigned me to work with the Criminal Investigation Division infiltrating drug rings and other rackets. This was not my thing. I had a hard time lying about my identity and it did not help that I never touched drugs so I was very uncomfortable. They needed females but I could be put to use better somewhere else.

Congratulations. First assignment, Germany. Away from everything I knew. I showed up and was nicknamed Private Benjamin. I was tasked with 12 to 15-hour patrol days and nights responsible for enforcing the Post Commander’s rules and regulations. I was 19 carrying a side arm and had authority most 19-year-olds couldn’t fathom. For any accident that involved an American within 200 miles I would drive out in my VW van with no heater and a blanket draped over me. I’d get out, wipe snow off signs, and arrive to some horrific scenes thanks to the autobahn and no speed limits. The Polezi refused to show up so I had to handle the situations; my first taste of being a first responder and having to show calm and exude control of situations. Our wartime mission dealt with POWs, security and convoy assistance. As the lowest ranking, I got assigned an M60 machine gun then a SAW and had to sleep with this metal thing in my sleeping bag. I was so cold at times I could barely get my fingers to work to shoot, but it’s amazing how warm it gets once in use. After winning over my superiors they assigned me to work with the Criminal Investigation Division infiltrating drug rings and other rackets. This was not my thing. I had a hard time lying about my identity and it did not help that I never touched drugs so I was very uncomfortable. They needed females but I could be put to use better somewhere else.

Next assignment, Fort Dix, New Jersey where a major highway ran right through the middle involving many drug and alcohol busts. I became a patrol supervisor and was promoted to Corporal. I enjoyed my job as it was something new every day. However, I was now ready to go back to college. In Europe I got to travel all over the place and it opened me up to learning. I thought, “If I am going to continue in the Army, why not become an officer and get my degree?” I applied for a scholarship program and was released from active duty to become a cadet. I chose the University of Hawaii, nice beaches and cool drinks here I come. I arrived as a sophomore and had to wind down a bit from my service time. It did, however, give me a leg up as I already knew the basics. As a junior is when we’re really tested, and I learned early that leadership really is an art. What works for one group does not work for another. I had to adjust my style in order to influence and get things done. Most of my fellow cadets were from the islands and I was a mainlander who was a bit more tightly wound. I excelled and became the Cadet Commander as a senior. I made sure they understood how to show up on time, what doctrine was, what to expect in the Army and more. Again, many did not like this but later I heard from many that they now understood why I was as hard on them as I was. My goal was to prepare them. I graduated number one in my class and got my choice of branches. I chose aviation. As a Military Police I used to watch them fly all around as I drove and I thought it would be so cool to see things from the sky.

In flight school I had no idea what to expect. The first six months were basic skills and you would see 10 helicopters hovering, horribly, all over the airfield. Half the day was learning how to fly in the aircraft and the other half was academics. It was an awakening as neither I, nor many others, had any idea how much work this would be. Topics included physics, mechanics, math, anatomy, meteorology, aerodynamics, electronics and more. It was essentially everything and anything that affects the factors of flight. To blow off steam the class would go to Panama City, Florida on the weekends. I especially loved it when I was in civilian clothes and my male classmates behind me wore their flight suits because we all know they join to wear flight suits and get chicks. I would ask them lots of questions and feed a bit into their ego. It was always funny when I would see those same guys later on the airfield and I was wearing that same exact flight suit, and ahead. Who knew? Pass, now onto phase two.

In flight school I had no idea what to expect. The first six months were basic skills and you would see 10 helicopters hovering, horribly, all over the airfield. Half the day was learning how to fly in the aircraft and the other half was academics. It was an awakening as neither I, nor many others, had any idea how much work this would be. Topics included physics, mechanics, math, anatomy, meteorology, aerodynamics, electronics and more. It was essentially everything and anything that affects the factors of flight. To blow off steam the class would go to Panama City, Florida on the weekends. I especially loved it when I was in civilian clothes and my male classmates behind me wore their flight suits because we all know they join to wear flight suits and get chicks. I would ask them lots of questions and feed a bit into their ego. It was always funny when I would see those same guys later on the airfield and I was wearing that same exact flight suit, and ahead. Who knew? Pass, now onto phase two.

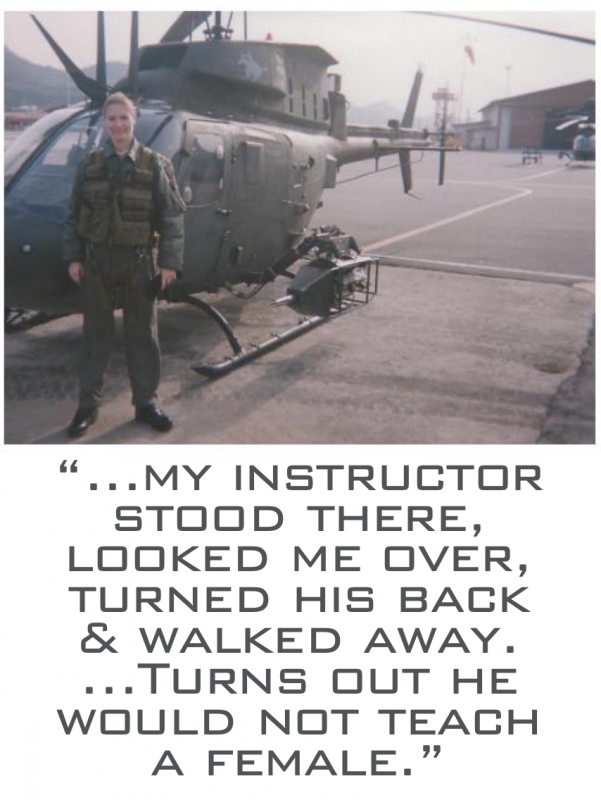

Basic Combat Skills is where you had to learn tactics and how to integrate them into the big picture of multiple moving parts. Pass. Now I got to choose my airframe. I had set out to be an Apache pilot but as chance had it, the scout mission was just about to open up to women. The airframe was the Kiowa Warrior, the most technologically advanced airframe in the Army inventory armed with Hellfires, 2.75 inch rockets and a .50 caliber gun. The airframe has a sight that can see 10 kilometers, day or night, away and laze targets. It was the last airframe, in any service, to allow women to fly. The cavalry mission appealed to me right away. It was not a question, I was going to lead from the front! Day one of training I walked out on the tarmac and my instructor stood there, looked me over, turned his back and walked away. Perhaps he had to go to the bathroom? Time passed, he never came back. Turns out he would not teach a female. I was confused. Having been raised with the belief I could do anything and being a girl did not matter, it was one of my first tastes of gender bias. Much more was to come. Perseverance is the name of the game. Watch out, Cavalry.

My first assignment in aviation I was sent to a hotspot in South Korea. Just a year prior a Kiowa pilot was shot out of the sky for flying to close to North Korea. It was apparent the war never really ended from the 1950’s, just put on hold. This was serious. I was in the Second Infantry Division, in a heavy division cavalry unit closest to the Demilitarized Zone with nothing around but landmines, bridges set to blow, cemeteries and dog farms. Not only was I part of the first group of females to graduate as an aeroscout; I, along with a small handful of other females, was the first at Camp Garry Owen, which at the time did not allow women.

Women were not wanted and the guys made no attempt to hide it. One of the first things I heard, and they did not know me from Adam, was, “Take your fucking tampons and get the hell out of here!” How do you respond to that? These were my subordinates and I was to lead them. This was definitely a leadership challenge; my prior service helped me. I took a deep breath and walked away. Clearly they had a problem but for no other reason than perhaps feeling less manly because a woman was doing the same job? Who knows? One month later I was standing in front of my formation of men, still sensing animosity. I turned around, faced them and asked, “What is the problem here guys?” After some hemming and hawing, one guy spoke up and said, “Well ma’am, if we crash and the aircraft is on fire I don’t think you can get me out.” I thought for a second. Is that it? It all comes back to the physical with men. These guys clearly underestimated my athletic ability and mental toughness. They had no idea and just assumed that a 125-pound female couldn’t possibly be strong. I simply walked to my biggest guy in the formation, about 220 pounds, lifted him in a fireman’s carry position on my back and shoulders and proceeded to walk about a quarter mile to the flight operations center and dropped him at the step. I returned to the formation, found their jaws completely dropped, and asked if I could move on. Dumbfounded, they moved on and had nothing to say after that. I began earning their respect and for those still not on board, I had the senior Warrant Officers police them up. At one point while leading a convoy to gunnery I had to exit my vehicle and pull road guards into place at a dangerous intersection. I needed to get my 10 trucks of fuel, ammo and supplies downrange, safely. When I walked out from the back of my vehicle, a Korean driver cut the corner and struck me. I flew over 100 feet in the air landing on my head and back. I remember blacking out and feeling my legs swing out from under me. I immediately came to, sat up, wiggled my fingers and toes, and my men rushed to my aid thinking I was dead. The helmet I was wearing, the same one all my troops complained about wearing while I insisted, cracked down the center and saved my life. I got up and continued my mission. Word spread and even I was dumbfounded that I was able to walk away with minor injuries. I got in my helicopter the next day and had the highest gunnery qualification score in the unit.

Women were not wanted and the guys made no attempt to hide it. One of the first things I heard, and they did not know me from Adam, was, “Take your fucking tampons and get the hell out of here!” How do you respond to that? These were my subordinates and I was to lead them. This was definitely a leadership challenge; my prior service helped me. I took a deep breath and walked away. Clearly they had a problem but for no other reason than perhaps feeling less manly because a woman was doing the same job? Who knows? One month later I was standing in front of my formation of men, still sensing animosity. I turned around, faced them and asked, “What is the problem here guys?” After some hemming and hawing, one guy spoke up and said, “Well ma’am, if we crash and the aircraft is on fire I don’t think you can get me out.” I thought for a second. Is that it? It all comes back to the physical with men. These guys clearly underestimated my athletic ability and mental toughness. They had no idea and just assumed that a 125-pound female couldn’t possibly be strong. I simply walked to my biggest guy in the formation, about 220 pounds, lifted him in a fireman’s carry position on my back and shoulders and proceeded to walk about a quarter mile to the flight operations center and dropped him at the step. I returned to the formation, found their jaws completely dropped, and asked if I could move on. Dumbfounded, they moved on and had nothing to say after that. I began earning their respect and for those still not on board, I had the senior Warrant Officers police them up. At one point while leading a convoy to gunnery I had to exit my vehicle and pull road guards into place at a dangerous intersection. I needed to get my 10 trucks of fuel, ammo and supplies downrange, safely. When I walked out from the back of my vehicle, a Korean driver cut the corner and struck me. I flew over 100 feet in the air landing on my head and back. I remember blacking out and feeling my legs swing out from under me. I immediately came to, sat up, wiggled my fingers and toes, and my men rushed to my aid thinking I was dead. The helmet I was wearing, the same one all my troops complained about wearing while I insisted, cracked down the center and saved my life. I got up and continued my mission. Word spread and even I was dumbfounded that I was able to walk away with minor injuries. I got in my helicopter the next day and had the highest gunnery qualification score in the unit.

Part 2 of 6

Towards the end of my tour I had set out to earn my spurs, an old cavalry tradition which signifies you are a cut above. This consisted of three days of physical hazing, meeting with a board of senior leaders to answer anything and everything about Cavalry tradition, and employing skills needed to meet the mission. For example, it could be a scenario where I would use my land navigation skills and find certain points. Upon arrival, the scene was some kind of chaos and you had to act under pressure. Or, it could simply be finding the right terrain to watch convoys and their movement to report back to headquarters. This involved carrying heavy equipment such as packs, radios, water cans and more. Prior to the spur ride they broke us into teams. No one wanted me, the female, on their team. Most of the teams were tankers stationed about 20 minutes away from the airfield. We did not know each other. There were a few aviators in the mix. I was assigned and the sighs were heard from my group as if they were expecting to have to tote me around. In contrast, at the end of the three-day event, the rater who was with our group from the start was absolutely flabbergasted at my performance. I steered the guys in the right direction when they became lost (a skill I learned well as an enlisted soldier thanks to a former commander), and carried the biggest guy’s rucksack on top of mine because he hurt his ankle and was always the first to get up when needed. The guys were slow to move and tired. It was, after all, 3 a.m. and they had been through days of physical and mental tests. Upon our return to the endpoint, the chain of command had been made aware of my efforts and I had it a bit easier from there. My team stopped looking at me as a female and began seeing me as a teammate, exactly as it should be.

I was awarded my spurs and wore them with pride! One slight issue, women were not allowed to wear pants with their dress uniform, they only had skirts. It was the year 2000 and spurs looked absolutely ridiculous on heels with a skirt. I broke the rules and had a Korean tailor make my uniform pants like the guys wear. This is a big no-no in the service. Uniforms are important and you must stick to the regulation. When I showed up to the ceremony in pants, no one cared. “Looking good lieutenant,” is all I got from my senior leaders. That was liberating. The symbolism here was powerful. Integration is never easy, but it gets easier for those who come after us. We were blazing the trail. I learned early on that if baseless hatred gets to you, they win. I learned to overcome discrimination by working hard, being physically and mentally tough, and setting the example. Eventually, the same guys who did not want me there were the same guys not wanting me to leave. Earned spurs in hand, I left having made it easier for the women behind me and left the unit a better place.

I was awarded my spurs and wore them with pride! One slight issue, women were not allowed to wear pants with their dress uniform, they only had skirts. It was the year 2000 and spurs looked absolutely ridiculous on heels with a skirt. I broke the rules and had a Korean tailor make my uniform pants like the guys wear. This is a big no-no in the service. Uniforms are important and you must stick to the regulation. When I showed up to the ceremony in pants, no one cared. “Looking good lieutenant,” is all I got from my senior leaders. That was liberating. The symbolism here was powerful. Integration is never easy, but it gets easier for those who come after us. We were blazing the trail. I learned early on that if baseless hatred gets to you, they win. I learned to overcome discrimination by working hard, being physically and mentally tough, and setting the example. Eventually, the same guys who did not want me there were the same guys not wanting me to leave. Earned spurs in hand, I left having made it easier for the women behind me and left the unit a better place.

Congratulations, you are going to the 82nd Airborne Division. Wow, okay. I needed a tad of R&R as I was on alert the entire time in South Korea; for a year I was woken at all hours of the night and had five minutes to get dressed, throw on my gear, make it to the airfield and get my helicopter up and ready. No stress there. I went to Australia for a few weeks and became engaged to Chris, a fellow aviator I’d met years prior in flight school. It took nearly the whole two weeks to unwind. At the end of my stay, I became privy to the story of how he got the ring to present. Chris had ordered the ring to be delivered to Korea. Picture this, the FedEx truck pulls up to the gate, in the middle of nowhere, as the unit was on alert with an M1 Abrams tank pointed right at the entrance. Chris had told his First Sergeant (1SG) that if he ever saw a FedEx truck to do whatever he needed to do to get the ring. The 1SG saw the FedEx truck imminently leave and he began running down the road screaming at him to stop. The 1SG accomplished the mission, retrieving the ring and handing it safely off to Chris.

After my R&R, I was off to jump school. Talk about a sore body after two weeks of chilling. As an officer, you must be airborne qualified to be part of the 82nd Airborne Division. I thought it was strange; an aviator having to jump out of a perfectly good airplane? When was that going to happen? I learned that it happened a lot and it was an honor to be sitting next to colonels and privates alike. The Esprit de Corps at that unit was unlike anything I knew. We all had to go through crazy stuff together and it did not matter what you looked like or what your gender was. We are the all American unit. Welcome to jump school. Now do 10 pull-ups before you step over the line and begin your training.

After my R&R, I was off to jump school. Talk about a sore body after two weeks of chilling. As an officer, you must be airborne qualified to be part of the 82nd Airborne Division. I thought it was strange; an aviator having to jump out of a perfectly good airplane? When was that going to happen? I learned that it happened a lot and it was an honor to be sitting next to colonels and privates alike. The Esprit de Corps at that unit was unlike anything I knew. We all had to go through crazy stuff together and it did not matter what you looked like or what your gender was. We are the all American unit. Welcome to jump school. Now do 10 pull-ups before you step over the line and begin your training.

I had the Cavalry brass insignia on my collar versus aviation and that got the attention of many. As usual, a few of the macho men types tried to break me, make me cry. Not happening. The majority of the men were cool, but I had come to expect a certain level of grief for being a cavalry officer, and a woman to boot. Some of the Navy Seals were the most supportive because they knew I could keep up; that was surprising to me. I thought they would be the hardest to win over. However, they are pretty secure in their own skin and appreciate hard work. It is tradition that the highest rank jumps out the door first. Lead from the front. Turns out, in my group, I was the highest ranking. I was what is called the chalk leader. You are standing by the door circling the drop zone and have to stare at the ground and throw any fear you may have out the window. Green light, go. No hesitation.

Scouts always lead from the front. Airborne!

Each unit got easier as my reputation preceded me. Senior leaders wanted me in their Cavalry units. However, at a level above them, so did the Brigade Commander as she was a proficient staff officer who managed 2,500 personnel, $75 million in equipment and over $200 million budgets and contracts. This hurt and helped me. I wanted to fly more and was requested, but kept getting pigeon-holed into logistics and contracts. At each location, there is no way the boss would let me out of the logistics position because I kept the aircraft flying, the unit out of trouble and the soldiers ready. In protest for all my hard work, tactfully, I demanded to go to the Advanced Cavalry Course taught by armor officers. Women were not allowed. After six months of hounding, my boss finally gave in. I was signed up and was Cavalry through and through. I was excited to learn so I could be better equipped to lead my men.

Again, being a bit naïve, I walked into the class and was completely ignored. A young officer grabbed me by the collar, threw me up against the wall and said that I didn’t belong there. None of the other men did a thing. No worries. They did not know who they were dealing with. Instead of whining or stating my case, I understood how to fight fire with fire, how men respond. Physically.

Now, women would not do this, but if you impress men physically, you are in. I reached out to him, grabbed him by the collar, and pinned him on the ground in a position from which he was not getting up. Clearly he did not know that I was an MP and was often used as a demonstrator on how to take a man down despite size. Now I was ready. Physical prowess, check. Mental toughness and expertise was still ahead of me. I ended up teaching half my class how aeroscouts integrate with ground forces because I lived it in Korea. I understood Cavalry tactics more so than most thanks to that assignment. I graduated, got my certificate and moved on. Turns out I was the first female to ever graduate from that school. It was never my intent to be the first, but it kept happening.

September 11th, 2001. A day that changed the nation. I was working in my office with a long line outside my door and got a call that a plane hit one of the towers. Why were they calling me about this unfortunate accident? Little did I know, like the rest of the country, the gravity of the situation.

September 11th, 2001. A day that changed the nation. I was working in my office with a long line outside my door and got a call that a plane hit one of the towers. Why were they calling me about this unfortunate accident? Little did I know, like the rest of the country, the gravity of the situation.

The second call, “You may want to take a look.” Two planes now each targeting the Towers. What? Okay, let’s turn the TV on. The rest is history.

I slept in my office for two nights straight as the base was locked down. No one knew how to handle something like this. Of course the 82nd Airborne Division was the first to get the call, they are America’s 911 force with the ability to deploy anywhere in the world within 18 hours. As the senior logistician for anything aviation, my world became very busy. Nothing moved in Afghanistan without air assets due to the terrain and scarce roads which were mostly controlled by the Taliban.

Then came my next assignment at the 10th Mountain Division where I was pushing guys out to Iraq, bringing them home and co-managing the effort in Afghanistan. While there, the pace was rapid keeping up with troop demands in the far reaching areas of the country. I had to work with locals, contractors and leaders in order to skillfully get supplies through Taliban strongholds. They were not used to taking orders from women but they were respectful.

While there, I witnessed things most American’s will never have to. The land is littered with landmines left from the Russian invasion in the 1980s. I organized a food and clothing drive for local kids, and while I was distributing the items with a small team, attacks followed. You can’t really trust anyone in a time of conflict. Also, tall mountains made for some hairy flying. Most flight corridors were in between two tall mountains and there were men at eye level (about 7,000 feet) waiving to you with a radio in one hand and a rocket-propelled grenade launcher in the other. It was unnerving to say the least. I was able to determine very quickly that communications were terrible due to terrain and antiquated systems.

Because I worked in contracting, I was able to research state-of-the-art radio systems and pass my request up through the highest levels of leadership in country to get the $20 million in funding to equip all my aircrafts and increase effectiveness. This saved countless lives in the air and on the ground.

While on base, rocket attacks happened frequently. Rest was minimal and when it happened, my wooden shelter was right off the airfield with loud jets and helicopters flying non-stop. If you want to call it lucky, I had to leave earlier than the rest of my unit to bring the other half back from Iraq. It was a fast-moving train of events and you either kept up or got left behind. People forget that every time an aviator straps in their aircraft, things can and do go wrong whether it is training or war. When something catastrophic happens, there are investigations because the Army, manufacturers and family members want answers. I have had to investigate crashes and similar traffic accidents in Germany. It was hard to process, especially if I knew the people. Lest we forget.

Part 3 of 6

Chris and I finally got married and a few years later came our first son. We planned it so I would be pregnant in a non-operational position during an eight-month leadership course. Noah was born upon arriving to my next assignment at the 10th Mountain Division in upstate New York. My mother decided to help since Chris and I were both serving and someone needed to be with the new baby; it really takes a village to raise a family.

Chris and I finally got married and a few years later came our first son. We planned it so I would be pregnant in a non-operational position during an eight-month leadership course. Noah was born upon arriving to my next assignment at the 10th Mountain Division in upstate New York. My mother decided to help since Chris and I were both serving and someone needed to be with the new baby; it really takes a village to raise a family.

I left Ecuador, where I worked on some amazing projects with international organizations to help save the original watersheds, the rainforest and its indigenous people. I was selected to become the first female cavalry commander while I worked as the senior logistician for the unit, but it kept getting pushed back due to logistical needs. The commander I was to replace had already been shot down three times, and survived each. I was told the command was going to be delayed a year, and then I became pregnant with my second son Ayden.

Upon giving birth and successfully delivering him, I went back to fighting shape quickly, ready to take my command. However, a new boss came in and would not release me because I knew the job too well and he needed my continuity. Again, my command got pushed back. Getting fed up as I saw some of my less-than-stellar peers get their commands, I pushed for release from the staff position.

The cavalry units were fighting for me, but the senior leaders would not let it happen. I then decided I had done my time and began thinking about leaving the service. Additionally, the more time I had to think, the more I realized I wasn’t feeling as invincible as before. The dangers of my job were prevalent, friends were dying and I decided I needed to be there for my two young boys.

It was an extremely hard decision to leave the service because the young women pleaded with me to stay. They needed to see good women leaders in positions of authority as there were none. I never had a female mentor. I had some great leaders along the way, but never women. I was part of the first wave to blaze the trail. I never felt I was missing anything, but it is important for people to see others who look like them in leadership positions; it empowers them to aspire to be there.

Despite the tugging of emotions, I was honorably discharged and began dipping my toes into a completely unfamiliar world. I had been in the military my whole adult life— 14 years. Concepts like teamwork, integrity, mission accomplishment, sacrifice, leadership, camaraderie and more resonated heavily with me. I entered civilian life.

My husband had switched from the Army to a pilot in the Coast Guard when I got out. We packed up and moved south to Miami, Florida with a baby and a toddler. Everything was new to the both of us; civilian life, a new branch of service and a new place. We showed up to a unit function and I knew some of the guys because we had served together in the Army. They, too, made the switch to Coast Guard.

I felt a bit of camaraderie coming back and was really enjoying the conversations when I noticed out of my periphery snide looks from the wives. Who is this lady talking to my husband? Why are they laughing so much? Boy, she is brash. Okay, I was used to jealous wives but I made sure to get to know my soldiers’ families so they did not view me as a threat. Often times, I would have to call my guys in the middle of the night to come in for a urinalysis drug test. Until the women knew me, I had to deal with the snotty, “And who is this?” My male peers never had to deal with this.

At the party I had an impactful realization that I was not one of the guys anymore. I was one of the girls. What does that mean? I owned my femininity in service and saw it as a strength. However, it was clear that femininity was different out here. I would rather hang with the boys; it was what I was used to. I felt torn.

At the party I had an impactful realization that I was not one of the guys anymore. I was one of the girls. What does that mean? I owned my femininity in service and saw it as a strength. However, it was clear that femininity was different out here. I would rather hang with the boys; it was what I was used to. I felt torn.

Where did I belong? With the guys or the girls? Men go from being a guy to a soldier to a guy. Yes, they certainly have integration issues, but they don’t have to learn how to be a guy again. Women go from being a woman to a soldier and then have to consider what being a woman is in civilian society. It was one more thing to think about. Why is this so difficult?

I felt unprepared for the dreaded transition we all hear so much about— a soldier leaving the military. It was a completely different culture. How was I to fit in? What was I going to do professionally? There was no one to talk to who understood. I had two kids, a husband, and had to move yet again. My husband was still in the system; I was not.

I decided to work on an Executive MBA in Miami. Each classmate had to have at least eight years in their profession so I figured I could learn from them about the corporate world. My classmates were overwhelmingly from somewhere in Latin America with the exception of one Irish guy. I didn’t have much in common with any of them. I felt like an outsider but wanted to learn. My approach was systematic and efficient. When working in groups I expected others to keep up, but very few could.

When I had to sit through leadership courses I winced under my breath. What do these people possibly know about leading people when they are hungry, away from their families, tired, stressed and not in a controlled environment, having to be flexible at every turn? What do they know about getting broad orders and figuring out how to get it done creatively? What do they know about getting people to perform their best, pushing people to the absolute limit?

I was distancing myself because I could not relate to their problems which seemed so miniscule to me. They would make comments about military people being like robots. Sure, however, if they respect you, they will go above and beyond the bare minimum. If they do not like you, they will not go out of their way to do a good job, and that is when accidents happen. We can’t afford accidents in the military. Lives are on the line. I ask you, if your employee doesn’t do what they need to, do they get fired? They will not work hard for you if they don’t respect you.

It’s no different, except I don’t have the luxury of firing them. I get what I get and have to make them great. They come to us from all walks of life and we become their family. We get to know them. If they have issues back home, we let them take care of it because if not they are not effective. We develop and mentor them. Do you guys in your corporate positions really care and develop your people? Do you get them to perform in a way they never thought possible? We leaders in the service do. Twenty percent of every dollar that was spent on me was for professional development. Show me any company that does that for their employees.

It’s no different, except I don’t have the luxury of firing them. I get what I get and have to make them great. They come to us from all walks of life and we become their family. We get to know them. If they have issues back home, we let them take care of it because if not they are not effective. We develop and mentor them. Do you guys in your corporate positions really care and develop your people? Do you get them to perform in a way they never thought possible? We leaders in the service do. Twenty percent of every dollar that was spent on me was for professional development. Show me any company that does that for their employees.

It was a bit abrasive as this was my world they were discussing. I did not make friends easily. Also, as a woman, the brashness that came with joking, taking criticism and dishing it back was not well received. In the military, harassing each other in a funny way is acceptable and keeps you going with laughter. Being cavalry made it even worse; those are some of the most machismo guys around. I kept my head down and worked towards good grades.

The class had to go to an internship in India. I left a week ahead of my classmates to explore because I was struggling with integration. I hiked the Himalayas, ate great food, went to Tibetan refugee camps and did some soul searching. I needed that alone time. I then met up with my classmates as they travelled all over visiting various businesses.

One day we were in our hotel and I heard a loud explosion. I immediately went into “go” mode, meaning I began doing what I was trained to do: be cautious, look around for clues and try as best I could to fit in and not stand out. It was a bomb placed on the railroad tracks targeting American businessmen. Typical. Pakistan and India have had conflict for years, but interestingly they are targeting Americans.

My classmates could care less. I spoke to the university lead and said I was uncomfortable riding around India in the big, shiny white air-conditioned bus and would not ride in it after the explosions. He called me crazy as if I was suffering from some sort of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Really? I asked him to order a less obvious, ugly van or bus for the class. He refused.

I was ostracized and my classmates thought I was a bit crazy. They had the “go with the flow” mentality. That was not the way I was raised. I grew up learning not to put yourself in danger if you can avoid it and to pay attention to what is going on around you. I ordered a taxi and it followed the bus for days about 10 car paces behind.

I spoke a lot to the local taxi drivers and they said things were not normal. The markets were empty, tensions were high and they were uncomfortable. These are signs. I was not trying to act smarter than my classmates like one person said to me; I was just trying to fit in and the last thing I wanted to be was a target.

There were no other big white air-conditioned buses going around India, and it was a bus full of American business students. Why was this so hard for my classmates to comprehend? All it would take is one lone guy placing a sticky bomb on the bus in traffic. Thank goodness this never happened and all was okay, but I had to do what I had to do despite the social fallout from my classmates.

A few years later there were mass shootings at the hotel my class stayed at in India targeting foreigners, an example that my heightened state of alert may not have been a bad thing. I am too familiar with being a target and was trained to mitigate risk. Why is this so hard for others to see?

Oh, the cultural divide. I began to feel the differences and, like many veterans, tried to internalize it. Is it me? Am I the problem? What is wrong with me? Can’t I just fit in? I want to. No, you know what, I am fine. I feel I am more prepared and see the world clearer. I can solve a problem and see ten steps ahead of them. My skills are valuable but no one bothers to ask about my background.

They can’t possibly understand. They think I am a cog in the wheel of mindless actions. What’s wrong with them? I am not going to waste my time. These people are kind of afraid of me and think I am going to flip out because that is all they hear, PTSD and mental health problems with veterans. They are off the mark.

So begins the isolation stage of the transition, the inability to connect.

Part 4 of 6

With my EMBA close to completion, I was offered a senior level job at a logistics company in Miami. They needed me to lead and grow the government market. Even though I kicked and screamed about being pigeon-holed in logistics and contracting, it sure was a marketable skill. I used to buy everything, from BBQs and sunglasses to furniture and aircraft armor. I worked with the contracting officers and comptrollers who handle the big budgets routinely when I had to equip my units in the U.S. or abroad. Now companies wanted to know how to get to the person I used to be.

With my EMBA close to completion, I was offered a senior level job at a logistics company in Miami. They needed me to lead and grow the government market. Even though I kicked and screamed about being pigeon-holed in logistics and contracting, it sure was a marketable skill. I used to buy everything, from BBQs and sunglasses to furniture and aircraft armor. I worked with the contracting officers and comptrollers who handle the big budgets routinely when I had to equip my units in the U.S. or abroad. Now companies wanted to know how to get to the person I used to be.

It was obvious people had no clue how to deal with federal buyers. I could build a section and plan out their approach. Sure, sign me up. I will take the job. For the first time, I had to think about what I was going to wear. It had been uniforms day in and day out forever. Not a big shopper, I found outfits on mannequins that looked good and showed up early, because if you are not early in the Army you are late.

No one was there when I got there. The boss pulled up, happy to see me and said I was looking sharp. I thought nothing of it. I had to be very guarded; you never give off signals in the Army. My boundaries were disciplined. In Miami, flirtatiousness abounded. I wanted to be taken seriously and flirting would have destroyed that. I worked hard and the boss loved me, but I was in my own bubble. No one knew what I was doing or had any idea about government. I was not connecting with the workers. It was not a good fit.

I left after a year. Corporate America was not my thing. However, during this time, Oprah and The White House Project named me, along with 50 other women around the country, a woman with the background and drive to change the world. We were all sponsored and flown to New York to collaborate with community, government and private leaders who inspired me to continue to serve.

Degree in hand, I decided to go it alone. My family was now moving to Jacksonville, Florida. The need for government business development was there. I researched the market and found many unqualified people charging a fortune to break into this space. People just don’t know what they don’t know. You can’t just jump in. You have to understand the buyer’s language. I knew within 30 seconds if I would work with a vendor or not while serving. Why not prepare people correctly, especially if they were willing to pay for my expertise?

Degree in hand, I decided to go it alone. My family was now moving to Jacksonville, Florida. The need for government business development was there. I researched the market and found many unqualified people charging a fortune to break into this space. People just don’t know what they don’t know. You can’t just jump in. You have to understand the buyer’s language. I knew within 30 seconds if I would work with a vendor or not while serving. Why not prepare people correctly, especially if they were willing to pay for my expertise?

I formed an LLC and began getting out there speaking at local chambers of commerce, business events and similar engagements. I started forming connections that led to leads and secured my first contract within two months of starting my company with a solar thermal manufacturer. They were a great client and I connected with my contact who was a “tell it like it is gal” who was right up my alley. As in battle, you need to know your conditions; who is to your left and right, enemies, communications and more. In business, it is imperative to know your competition, who is buying, what their messaging is and how to speak in a way that resonates with the buyer. I took my military skills of analysis, planning and problem-solving and applied them to my work on the outside. I began to get more clients and before I knew it, I was making over $300,000 in revenue.

Seasoned, experienced people at venture capital firms and billion-dollar companies said that I produced the best sales and marketing plans they had seen in their careers. Yes, I earned an EMBA and it helped me with understanding that language, but it was my military strategic planning skills that earned me praise. I began hiring people and brought in a partner. I saw potential in this partner, but she had little experience in the contracting space at this level so I did what I knew best: I mentored and developed her over a year.

I would put her in front of the customer without getting involved except to guide her from the sidelines. This turned out to be a mistake. I trusted her as I trusted my military brethren. She got greedy, wanted her own business and took the clients because all they knew was her. It was a lesson that taught me greed trumps loyalty and to never expect thanks for training someone and introducing them to a skill that provides them a livelihood.

It turns out that when she came to me demanding 50 percent of the company and was turned down, she had already been moving company documents electronically for over a month. She was taking proprietary information to create her own business. Lawyers got involved and from that, I came out on top and my former partner had to pay all legal fees. It was painful, not necessarily the monetary part of it, but the realization that people do not behave as you think they should. If I was brought in, trained, paid more than the founder and given the opportunity to be the front man not being micromanaged, I would have been grateful.

They say in business you actually earn your tuition by doing, not in school. The real world of business is cutthroat and most people work for the dollar, not the team or mission. I wondered over and over, could I have seen the signs? What did I do wrong? How could I have smoothed this over? How could I learn from this? It baffled me. I did not see this coming and was given no warning about my partner’s intentions. Bottom line, I chalked it up to a learning lesson never to be repeated. I became much wearier from that time on.

Despite this setback, I was named one of the top 40 people in the community under 40 doing well in business by the Jacksonville Business Journal. I started getting involved in advocacy. It is known that veterans are much more likely to continue service upon their release. I became a Commissioner for Jacksonville representing more than 650,000 women. Every month, community representatives would come in and discuss their specific issues such as young girls and women in the judicial system, healthcare discrepancies, and transportation issues for mothers working two or three jobs through the evening hours, women of color bias, employment and more.

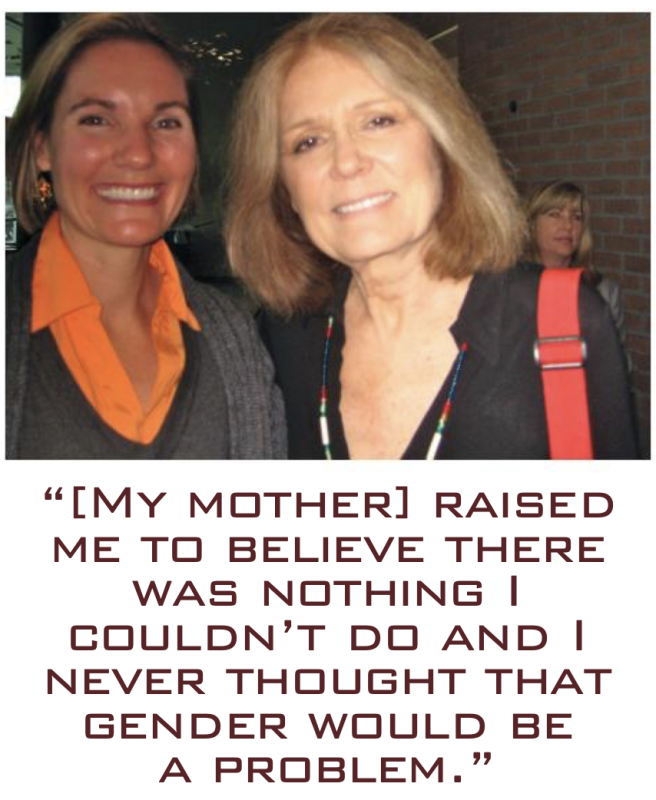

I never thought about a lot of this, I never had to. Having been a woman in a “man’s world,” I thought I understood discrimination and biased behavior. However, I realized I had a lot to learn from the women before me. As the youngest on the panel of seasoned women, the President had mentioned that Gloria Steinem was coming to visit us and all the women were excited. I, never afraid to admit I don’t know something, cautiously asked, “Who is Gloria Steinem?” Boy, the looks those women gave me were like knives cutting through butter. They explained that she had been a pioneer of women’s rights since the 1960s.

I never thought about a lot of this, I never had to. Having been a woman in a “man’s world,” I thought I understood discrimination and biased behavior. However, I realized I had a lot to learn from the women before me. As the youngest on the panel of seasoned women, the President had mentioned that Gloria Steinem was coming to visit us and all the women were excited. I, never afraid to admit I don’t know something, cautiously asked, “Who is Gloria Steinem?” Boy, the looks those women gave me were like knives cutting through butter. They explained that she had been a pioneer of women’s rights since the 1960s.

I went home and figured if anyone would know her, my mother would. My mother joined the Peace Corps when I was 18 and had always been fighting for causes. She raised me to believe there was nothing I couldn’t do and I never thought that gender would be a problem. My mother said, “Of course I know her. You marched on my back when you were a baby with her several times fighting for women’s rights.” It was at that moment that I realized I needed to know the women who came before me. Why didn’t I know my own gender history? I started paying attention. Even though I was blazing trails, there were many before me that made it possible for me to do what I did.

After five years of successful growth, I decided to keep only my favorite clients and move on to another venture. The next move was northern California. A former client of mine was very connected and respected in the Silicon Valley area. She approached me and asked if I would want to go into business with her. I did my risk analysis I had been so trained to do. Already a very successful business owner, check. Can teach me a few things, check. Is giving me the opportunity to get business through her contacts given that I am already a certified veteran-owned firm in California, check. In the field of logistics which I understand well, check. Data capture through smart people and equipment like drones, check.

It was a different kind of business. Not consulting per se, but the actual management of “stuff.” I had to start getting out there and meeting people in a way I did not have to before. There was much focus on sales, marketing and connections. Based on my work in business and the community, the Silicon Business Journal named me a Women of Influence. Like many veterans, I researched many groups on the internet that could help guide me along. There were plenty of veteran advocacy groups, many popping up every day. It is no wonder veterans isolate themselves; it is very confusing to know who to sift through. Who is credible? Where are they, thousands of miles away? Most groups centered on handouts, employment, mental health, adaptive construction for disabilities and everything VA. I was not interested in those. I was looking for peer groups in business, a grassroots approach and something I could belong to locally, not in D.C.

Part 5 of 6

It had been some years now since I got out of active duty. I had ‘transitioned.’ However, it was obvious to me that my veteran community was suffering and struggling to adapt to this new world on the outside. As I travelled the country on business, I would frequently end up sitting next to veterans on a plane. Once the veteran connection was established, when they could get past my gender and realize I was in the fight alongside them, they would offload their personal stories. Many had never shared these things with their own families. I would listen and advise if possible.

It had been some years now since I got out of active duty. I had ‘transitioned.’ However, it was obvious to me that my veteran community was suffering and struggling to adapt to this new world on the outside. As I travelled the country on business, I would frequently end up sitting next to veterans on a plane. Once the veteran connection was established, when they could get past my gender and realize I was in the fight alongside them, they would offload their personal stories. Many had never shared these things with their own families. I would listen and advise if possible.

After years of this, it became apparent that something wasn’t working. Why was I constantly being bombarded with this heavy stuff? I tried ignoring it but then started dissecting the events. Veterans want to talk to veterans— not white coats, not federally-funded programs stemming around entrepreneurship where they handle hundreds of people led by a non-business owner, and not corporate America attempting to give them a job. They wanted connections with people who understood them. Perhaps being a female was also non-threatening and these guys could be vulnerable?

Many veterans don’t want handouts; they want purpose. They want camaraderie and miss a bit of the military culture. I went to the Veterans Administration (VA) and explained what had been happening, advocating that they should look into peer-to-peer methods more. I suggested that women veterans should lead programs, because in some cases men can offload their stories more easily to a woman. As a former Military Police prior to being an aviator, I dealt with disgruntled men all the time, but very rarely would they lash out at me, because of my size. They had to think about my position and they were not going to hurt me. I could talk them down without resorting to aggression to calm the situation. Perhaps male veterans have less to prove to a female veteran?

The questions I posed to the VA went unheard. This made me angrier. What are we doing as a society to help my fellow brothers and sisters in arms? They are suffering but they are extremely capable! National treasures. I dug into the research and found that throwing money at the problem wasn’t working. Billions spent on mental health yet less that 10 percent of veterans seek it and only a handful of them experience positive results. Male veterans were committing suicide at twice the rate of civilian men and women veterans at a staggering six times the rate of civilian women. Higher rates of addiction, divorce and mental health problems existed. Women veterans actually suffered higher rates of everything over their male veteran counterparts in every area minus addiction. Why? What is going on? It broke my heart because I knew them when they were ‘strong’ and confident.

The military trains service people well but does not help them transition in terms of what to expect appropriately. A month resume writing class and how to dress just doesn’t cut it. Pointing them to resources in which they get lost is not working. They have either military people that know nothing but the military or civilians who have never served. Where is the sense in that? Where can we find veterans who have lived in both worlds to help bridge the cultural gap? I looked into job placement, but the military suggests jobs veterans could be suited for from our grandfathers’ day, not the tech jobs of today.

The military trains service people well but does not help them transition in terms of what to expect appropriately. A month resume writing class and how to dress just doesn’t cut it. Pointing them to resources in which they get lost is not working. They have either military people that know nothing but the military or civilians who have never served. Where is the sense in that? Where can we find veterans who have lived in both worlds to help bridge the cultural gap? I looked into job placement, but the military suggests jobs veterans could be suited for from our grandfathers’ day, not the tech jobs of today.

These placement agencies get credit for putting a veteran in a corporate job but there is no follow up. Did we really help them when half are quitting by their first year and 74 percent quit by year two? I understand this because I went through it, the inability to connect with civilians. They don’t understand or value our background because they can’t comprehend it, or the veteran simply can’t express it in a way they understand. The mission focus, teamwork and integrity are lacking, the ability to work to task and not to time. It is no one’s fault; it is a simple fact of not understanding each world.

Veterans begin to feel like no one understands and they slowly remove themselves. If we do not catch them within three years of discharge, this is when problems arise. It is absolutely imperative for us to get this right. No more canned training programs taught by those who can’t bridge the two worlds. We must give veterans viable options and provide them purpose again. We must have veterans mentor other veterans because of that inherent respect and camaraderie. Veterans provide necessary and familiar tough love with one another.

While I was researching I found something astonishing. Forty percent of veterans are going into business for themselves as opposed to 10 percent during the Vietnam era. That’s it, of course! Veterans have the skills; they just need the guidance from other veterans. The majority of the Vietnam era veterans are starting to retire, leaving a huge void in the economy if we don’t let the younger generations know they are needed. The younger generations can take over the businesses through acquisition or other means. Now the older generation has more of a nest egg and their lives work is not all for naught. Many younger veterans don’t know what they want to do so this is a perfect opportunity. The veterans who know need organizations from which they can seek guidance in a meaningful way.

As my company grew and I landed some great contracts working on distribution projects for low-income energy efficient housing, delivering new parent kits to clinics and hospitals across the state of California and performing drone as a service for multiple industries seeking to improve efficiencies, I found an organization that helped me along the way called the Disabled Veteran Business Alliance (DVBA)-now the USVBA. It is the longest-running veteran organization focusing on entrepreneurship through advocacy, training and mentorship. There were seasoned veteran business owners as well as some start-ups, all looking to connect and help each other grow. It was the people that kept bringing me back with the long track record of success for our veterans.

I volunteered in San Francisco, and then became a Board member and eventually the first female BOD President working hard to incorporate both generations of veterans in a meaningful way. I found out quickly that this community is run by a lot of older gentlemen that are territorial instead of collaborative. These men had no idea what to make of me, but I was used to that. In order for the community to prosper, we have to collaborate and not reinvent the wheel, making it more confusing for veterans and supporters alike. There is plenty of business to go around and it is our duty to bring up the ones behind us-just as the Vietnam veterans did for us.

Along this journey, I got to know leaders from across the country doing right by veterans. They are out there but get lost in the noise. 42,000 organizations dedicated to veterans and their families. Too many. We need to alert transitioning soldiers about options and organizations so they know who to contact as they go through the cycle. Veterans attend school, work, quit, and either pick themselves up or fall prey to the negative statistics. Let’s get them on the positive side of the statistics. Offer them options like entrepreneurship, UN, USAID, DoS security missions making differences in communities, non profit and community work etc. Veterans often want to continue to serve, something other than themselves, after discharge. Corporate job placement should only be one of the options upon leaving.

Along this journey, I got to know leaders from across the country doing right by veterans. They are out there but get lost in the noise. 42,000 organizations dedicated to veterans and their families. Too many. We need to alert transitioning soldiers about options and organizations so they know who to contact as they go through the cycle. Veterans attend school, work, quit, and either pick themselves up or fall prey to the negative statistics. Let’s get them on the positive side of the statistics. Offer them options like entrepreneurship, UN, USAID, DoS security missions making differences in communities, non profit and community work etc. Veterans often want to continue to serve, something other than themselves, after discharge. Corporate job placement should only be one of the options upon leaving.

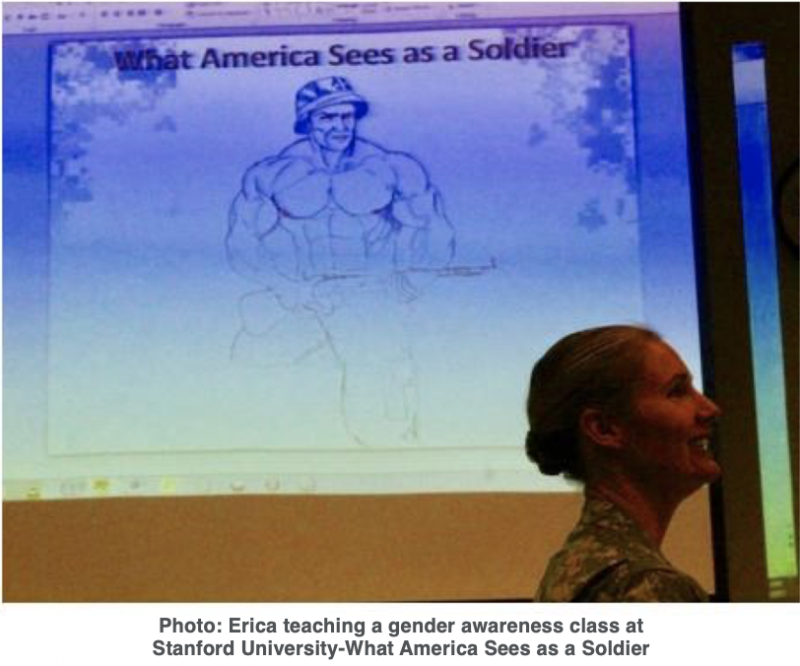

While speaking at Stanford University, I met the Lieutenant Colonel in charge of Army cadets for the region headquartered at Santa Clara University. He asked if I could share some of my combat arms experiences with the cadets, especially since the law to allow women in all combat arms positions had been recently signed into law. The Army had a plan to integrate women in areas they never served in previously over the course of the next three years. Since I was part of this movement only 10 years prior, my expertise could potentially prepare both male and female leaders for things to come from a firsthand account. I agreed and enjoyed the experience.

I came to find out that there was not one woman SROTC instructor for the entire northern California region at UC Davis, UC Berkeley, UCSF and other educational institutions. This baffled me. Where were the women behind me? One thing led to another and, after a seven-year break in service, I re-commissioned into the U.S. Army Reserve to help mentor the next generation. Many top leaders think they know, but unless you are a woman in a leadership position, you can’t know. I would give about 20 hours a month to the program and saw that not much changed in the way the Army approached gender. It consisted of mandatory sexual harassment and equal opportunity training.

Now having seen both worlds at this point, I was able to bring a touch of civilian knowledge to the program. I had seen the authors of “Men are from Mars, Women Are from Venus” and some other scientific types speak in Silicon Valley. I learned that men and women have scientific differences and it is no secret we approach things differently sometimes. Let’s be aware of these differences and respect the other gender. It’s all about balance.

From the beginning of mankind men would have to hunt, focus and show strength to protect their territory. Women would have to collaborate amongst mothers, aunts, grandmothers and children while maintaining the peace. Women are said to be better at multi-taskers and communicators, and pay attention to detail. Men can focus, are good at directions and are generally physically stronger. The military could use both.

I created a program to create an environment of cohesiveness. My cadets nominated me for National Instructor of the Year and I won. I did not have much time in my schedule to wear a uniform again, but I felt compelled to help where I knew there was a gap. It was very strange for me to put on a uniform again, which had changed twice since the last time I wore one during the height of Iraq and Afghanistan. I had to make sure I was physically and mentally prepared and began hitting the track to ensure I could keep up with those young cadets. I had no problem and maxed my physical test. But, unlike when I was in my twenties, I felt it for a few days after! Ouch. I never let them know that though. Over the years, you learn to never let em’ see you sweat. Served me well. Now I am entering another chapter of service myself-veterans and the next generation of Army leaders. A fire in the belly is what leads to passion. Passion to make a difference. To be part of the solution.

Login

Login